Overview:

This page will discuss the basics of making salami. Salami is one of those projects that may seem daunting at first. Grind up a bunch of meat, keeping it as cold as possible, add spices, salt, nitrates, and starter cultures…maybe some wine, maybe some spicy peppers, stuff it into an intestinal casing, let it ferment at a warm but not hot temperature for a number of days, and then let it hang at not quite refrigerator cold temperatures…what could go wrong, right?

There are a lot of options, and conflicting view points on how to best make salami. There are traditional variations; ways of making salami that vary from region to region, which result in different nomenclature being used to address what that particular salami is called. There are personal preferences; such as what percentage of spices is used and in what combination, how much meat to fat is used, how long it is left to dry, what grind is used to grind the meat, etc… And then there are issues of safety, whether or not to use cure #2 (nitrates) and starter cultures in order to jump start beneficial processes and hold potentially lethal ones at bay.

I am a huge proponent of understanding the history and nomenclature behind what we do. I think it is important to understand how things have been done, before we can understand why it is that way (the science behind it) and how we can improve upon it. However, I think it is important to remember that these recipes have been mutable throughout history. While certain cured meats products now have DOP status and require certain ingredients and processes, they haven’t always been made that way. If you take a trip to Italy, you will see well known DOP products have cousins that we have never heard of, being made right next door, that just never gained DOP status and therefore haven’t gained great acclaim.

Once we understand the history of what we are making, we can delve into the science of it a bit. And once we understand what is necessary and what is able to be changed, we can experiment and have some fun with it.

I will start off by saying that I am firmly in the camp of using modern day knowledge to make my salami making as safe as possible. Some will argue that is not traditional. Certainly, that is true to an extent, although historically many salami makers used natural products that carried out the same function in a less exact manner. However, people have died this way. Therefore, all of my advice will include nitrates, starter cultures, and minimum salt levels as set parameters. Feel free to disagree, but botulism and listeria are all too real, and I would like to avoid getting them.

Planning Phase:

The first step in salami making is the planning. You must procure your meat, weigh your meat, decide on the ingredients you will add, calculate how much you will need of each item, and weight them out and have them mixed and ready to go. It is important to keep everything as cold as possible during the salami making process, so I will usually freeze the meat and fat anywhere from 1-12 hours before working with it.

You can procure meat in whatever manner suits you. You can hunt for it, buy it from a local farm, or purchase it at a supermarket. The better quality the meat (and this is where knowing your local farmers and how they raise and fed their animals plays an important role), the better the final product will be. In cases where the meat itself is of fantastic quality, many people believe the simpler the added spices, the better.

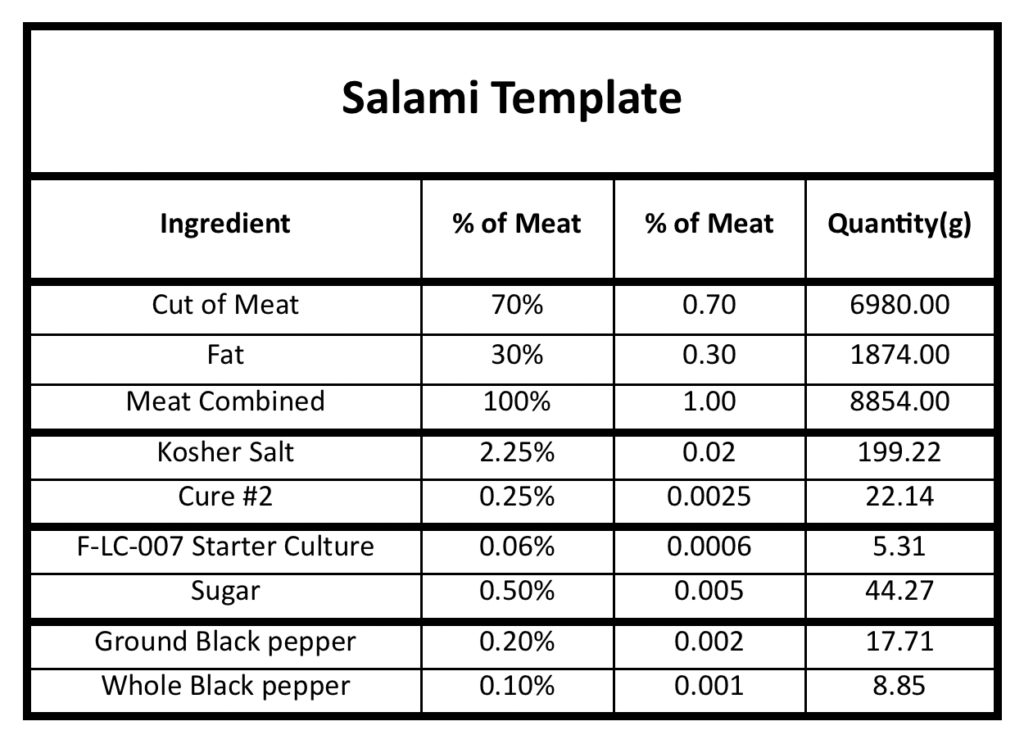

I have listed below a basic salami template:

In the above table I have listed the ingredient name, the percentage of the meat that that ingredient is typically added in, the percentage in decimal form to make computations easier, and then what that entails in actual amounts when multiplied by the weight of the meat. I use this table for all of my salami, playing with ingredients and their percentages, and allowing the spreadsheet to calculate the final quantity that I should add.

*Please note, I have since adjusted my preferred salt and sugar percentages as discussed below.

Meat and Fat:

The general ratio of meat to fat in salami will be about 70% meat to 30% fat. Pork shoulder generally has this ratio to it. People also use pork back fat as a source of fat. I tend to make a lot of non-pork salami, and have found that brisket fat is a very useful source of fat. It is possible to make salami with a lower fat percentage than 30%, but the salami will have a different texture than usual and may be more prone to crumble, and therefore I don’t advocate too strongly for it. It is possible to make salami with a higher fat percentage than this, and adding a higher fat percentage is really a personal preference. Some salamis (think ‘nduja) are made with a ridiculously high fat to meat ratio, which contributes to their deliciously sinful, melt in your mouth flavor and spreadable texture.

Salt and Cure #2:

The minimum necessary salt percentage is 2.50%* of the weight of the meat. This is one of those factors I wouldn’t play around with too much. It is a safe amount to add, and creates a product that is not overly salty.

As discussed in a separate post, Cure #2 is composed of salt, nitrates, and nitrites. It protects the meat from the growth of bad bacteria, such as C. botulism. I use it, I suggest you use it. 0.25% is an agreed upon percentage that is effective at preventing the growth of bad bacteria. I would not suggest adding less, since it will be less effective at lower concentrations. I would not suggest adding more, since nitrates are nothing to mess around with, and can cause significant issues if ingested in excess (it is colored pink to make sure that people do not confuse it with regular table salt, and consume it in dangerous quantities).

Starter Culture and Sugar:

The next important ingredient on my basic salami recipe protocol is the starter culture B-LC-007. The starter culture should be dissolved in a minimum amount of water, and added into the meat that is ground. I like this starter culture. There are others out there, and it’s worth researching what flavor you are looking for in your salami and which starter culture can help get you there. B-LC-007 contains a number of different bacterial strains. It is a mixed bacterial culture containing Pediococcus acidilactici, Staphylococcus carnosus, Staphylococcus xylosus, Lactobacillus sakei and Pediococcus pentosaceus. I think it is currently the best on the market, although these things change and it’s important to always keep an eye out for what is being developed and is available.

I absolutely think that starter cultures should be used in salami making. Using a starter culture insures that you get the growth of good bacteria that can keep bad bacteria at bay and prevent the spread of bacteria that can cause disease, such as listeria. It also makes sure that the bacteria cultures that grow will direct your salami down a flavor pathway that is enjoyable. Can you make salami without the addition of starter culture? Sure. Can it turn out great? Sure. Are your odds of creating a safe and delicious product as good? No. Starter cultures are an effective way to make safe, replicable, delicious products with little investment. I use them, I suggest you use them.

Sugar is an interesting factor is salami. It is not used to make your salami “sweet”. Sugar is used in order to provide the starter culture bacteria with fuel. Many people use dextrose or other forms of sugar that are more easily broken down by the bacteria. I use regular white sugar glucose, and have never had a problem with it. However, I am open to experiments with different forms of sugar, and admittedly need to do more research and experiments on the “best” type of sugar to add. Whatever form you add it in, 0.5% is usually a good percentage, and allows the starter culture bacteria enough fuel to get started and do their job.

Spices:

The final ingredient listed in my spreadsheet is ground and whole black peppercorns. I included these in this basic salami recipe after some debate. Pepper is not “necessary” in order to make salami in the way that salt is. However, most salami will contain a certain percentage of pepper in it. In simple salami, with good quality meat, many makers of salami will use only the simple recipe detailed above, including the pepper. Therefore, I left the pepper ratios in this for anyone who wants to try a simple tried and true salami recipe.

It also serves as a mechanism to talk about spice percentages. Generally, I add spices in the same percentages that I add pepper in. If I want the spice to be more pronounced, I generally add 0.2% of the weight of the meat. If I want a more subtle flavor, I will generally use 0.1% of the weight of the meat. If the spice is particularly pungent (think cloves), I will use less than 0.1%. If the spice is mellower, I may add more than 0.2%. If I want spicy salami and am using an ingredient like pepperoncini Calabrese, I may add it in percentages more than 0.2%. It’s also worth saying that sometime spices are better added as a powder, sometimes in their whole forms, sometimes in both. I have a spice grinder that I keep on hand to grind my salami cure spices, so that I can stock the whole ingredient and use it whole or in power form.

Meat Cubing Phase:

Once everything has been weighted, it’s time to cut the meat and fat into cubes that can be fed into the grinder. I tend to cut my meat into cubes that are about an inch by an inch by an inch. In the case of the fat, I use the form of the fat as a guide, and just make sure that if it is going to be ground that it will fit into the grinder, and if it will be hand cut, that I can cut it into appropriate size pieces.

There are differences in opinions on when you should mix the aforementioned cure and spice mixture with the meat. I don’t have a strong preference or understanding for when is best. I tend to either mix the cure/spices in with the cubed meat pre-grinder or the ground meat post-grinder. I have not assessed which of these has better results, and have had both work out for me in the past.

Meat Grinding Phase:

Once you have cubed your meat and fat, you can add your cure/spice mixture now or wait until post grinding. At this point, you are ready to grind your meat.

If you are looking for a more well defined salami, where you can see the meat and fat boundaries, you will want to grind your meat and fat separately, using a larger dye/course grind for your fat or perhaps even hand cutting it. You can use a smaller dye for the meat, or you may want to use a larger dye to grind your meat as well, which will result in a coarser final product with sharply delineated fat and meat boundaries.

If you are looking for a more homogeneous and uniform salami, you can grind your meat and fat together. You will want to use a smaller dye to grind your meat, which will result in smoother salami with less well defined borders between the meat and the fat.

I have made salami that fit both of these descriptions, and enjoyed both of them. There is no right or wrong way, just methods that either get you to your desired end product or not.

It is best to grind your meat in as cold of a state as possible for both safety and quality control reasons. Therefore, I put my meat, fat, and grinder parts in the freezer for at least 1-2 hours before I want to start. I try to work as fast as possible and return items to the freezer if I feel like they are getting closer to room temperature than I would like.

Once you have removed your materials from the freezer and assembled your grinder parts, feed the meat through the grinder using the dye that you have chosen.

Meat and Spice Cure Mixing Phase

At this point, you will have ground meat. If you didn’t previously mix in the cure/spice mixture, you will want to mix it in now as thoroughly as possible. You can add the dissolved culture into the mix now. If you didn’t grind the meat and fat together, at this point you will want you mix them together as well. You can either do this with your hands or in a stand mixer. You want to mix until the mixture is tacky and sticky, but not so long that the fat starts to warm up and lose definition.

Meat Stuffing Phase:

Once you have your ground meat/fat/cure/spice mixture it is time to stuff it into casings. I used to use my grinder to stuff my salami, but have since moved to a dedicated vertical stuffer and am immensely happy with the switch.

Based on the type of salami that you are trying to make, you will want to pick a casing that is the appropriate diameter. I have used both natural casings (beef middles and sheep intestines) and synthetic casing (collagen based) for this purpose. I have been happy with both of them, and suggest picking casings based on the diameter salami you are looking to make, keeping in mind that they will shrink with the meat as it loses weight over time. There are pros and cons to both natural and synthetic casings. My favorite lately have been sewn hog after ends, which have a nice diameter and thickness to them.

The first step is to mix your ingredients together thoroughly. Then, stuff the mixture into the stuffer, making sure to eliminate as much air as possible (although most stuffers have a mechanism to allow trapped air to escape).

Prepare your casings according to the instructions they come with (aka for most casings you will have to soak them in water before they are ready for use). Tie off one end, and gather the rest of the casing, pushing it down around the stuffing horn.

Use one hand to steady the casing around the stuffing horn, and another to crank the stuffer (or if it is automatic, to man the switch). It takes some practice to get a good rhythm down, but you should eventually be able to stuff your casing in a consistent and reliable manner.

Tie off the salami at your desired size. You can do this by twisting the casing and then using butchers string to keep this twist viable.

Continue this process until you have finished stuffing all of your meat. Once you have finished stuffing all of your meat into casings, use a sharp clean object, such as a toothpick, to puncture any air holes in your salami.

Meat Tying Phase:

After you’ve stuffed your salami, it’s time to tie it. You can either do this by hand with butchers twine, or you can buy netting for the salami. I do both, depending on how I want the salami to turn out and what I have available that day. Using the netting will result in more even compression while drying, while hand tying is more traditional.

Fermentation Phase (48-72 hours):

Temperature: 70-80 F/21-27C (strain dependent)

Humidity: 80-90% RH

Once all your salami is stuffed into casings, it’s time to allow the meat to ferment. This is where the starter cultures really play an important role. The warm, humid environment and abundant sugar for food, allows the start cultures to take off. Their growth will help to lower the pH which is protective against certain pathogenic bacteria. They will also start to develop the characteristic flavors that we associate with salami.

At this point, you can also start to spray your salami with mold spores if you so desire (I usually do when starting out new, once my chamber is inoculated with it, I don’t spray individual items anymore). Bactoferm 600 is a commercially available form of penicillium nalgiovense. This mold acts in a protective manner against detrimental mold, and imparts flavor to the salami.

Some people track their fermentation with pH monitoring (you want to see a drop to ~5.3 or lower), while others assume the starter cultures are doing their job and move forward after a certain amount of time. After attempting to track my pH in low budget ways and not having a ton of success, I have since moved into the second camp. I am sure I will spring for an expensive pH monitoring system in the future, but until then, I will use a set fermentation time that is not pH dependent.

Drying Phase (4+ weeks):

Temperature: 54F/12C

Humidity: 70-80% RH

After the salami has fermented for the appropriate amount of time, determined either by pH monitoring or simply time, the salami is moved into the curing chamber. The chamber should be set to its usual settings. The salami is allowed to dry over time, and can be pulled at as early as 30% weight loss. While I use 30% weight loss as my marker for whole muscle cures, I have found that I prefer my salami to go a bit longer than that, and usually pull them around 40% weight loss.

Initial Tasting Phase:

After the salami reach the 40% weight loss marker, I pull them from the chamber. I remove the casing, and wipe them down with either white vinegar or wine. I pat them dry after this, and slice them open to taste. After an initial tasting, I usually vacuum seal them, to allow for better equilibration, and will try them again in a few weeks/months.

This post has been a general overview of salami making. In future posts, I will discuss the particular recipes I have made.

Updates:

* I used to use 3% total salt, I have since cut down to 2.5% total salt, with 2.25% coming from kosher salt and 0.25% coming from the Cure #2. This is line with research showing that using modern methods this is an effective and safe salt cure %. I also used to use 1% sugar, I have since cut down to 0.5%.

Disclaimer: Meat curing is a hobby that comes with inherent risks. We can all do things to limit this risk by educating ourselves about the process and the utilizing the safest known methods to create our products. This website is for educational purposes only, and all experimentation should be done at each individuals own risk.