‘Nduja (en-DOO-yah) wanna do something fun today? Make ‘nduja! If you’re looking for something that is the opposite of subtle, that will kick you in the face and leave you smiling, look no further. ‘Ndjua is a fatty, fiery hot, smoked, spreadable salami that is perfect on some crusty Italian bread or as base for pasta sauce. The combination of spice, smoke, and fat will leave you constantly craving more.

Planning Phase:

The process of making ‘nduja may seem odd to you if you’re used to making traditional salami. The ratios you need to use may seem completely ridiculous. Don’t worry. If it seems excessive, it is. That’s the point. You’re going to want 70% meat and 30% pepper.

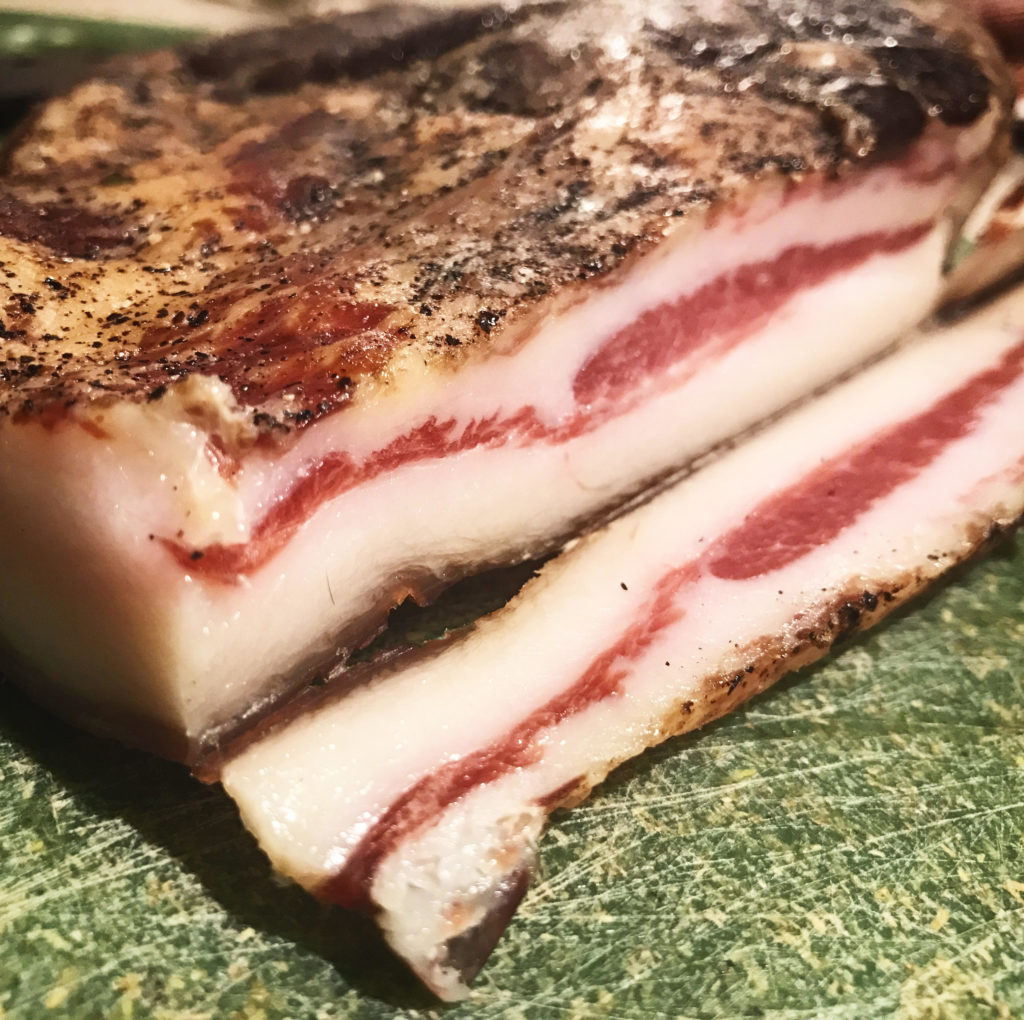

In the 70% meat fraction, you want 85% fat and 15% lean meat. No, that’s not a typo. This salami is mostly fat. There are a number of ways to get to this. You can use straight belly or jowls, which tend to have this ratio naturally. Or, you can use backfat and mix it with lean meat.

In the 30% pepper fraction, you can vary the ratios based on tastes. I used 50% sweet pepper and 50% hot pepper. (Just a note: There are a number of ways to make the pepper fraction for ‘nduja. Some people use dried whole peppers, others use dry pepper powder, and still others use paste. If you are using dried whole peppers, you will need to put them through your grinder first. Once they are ground, you can reconstitute them into a paste.) For mine, I used a combination of dry pepper powder and pepper paste to get to my 30% total pepper.

Cubing and Mixing Phase:

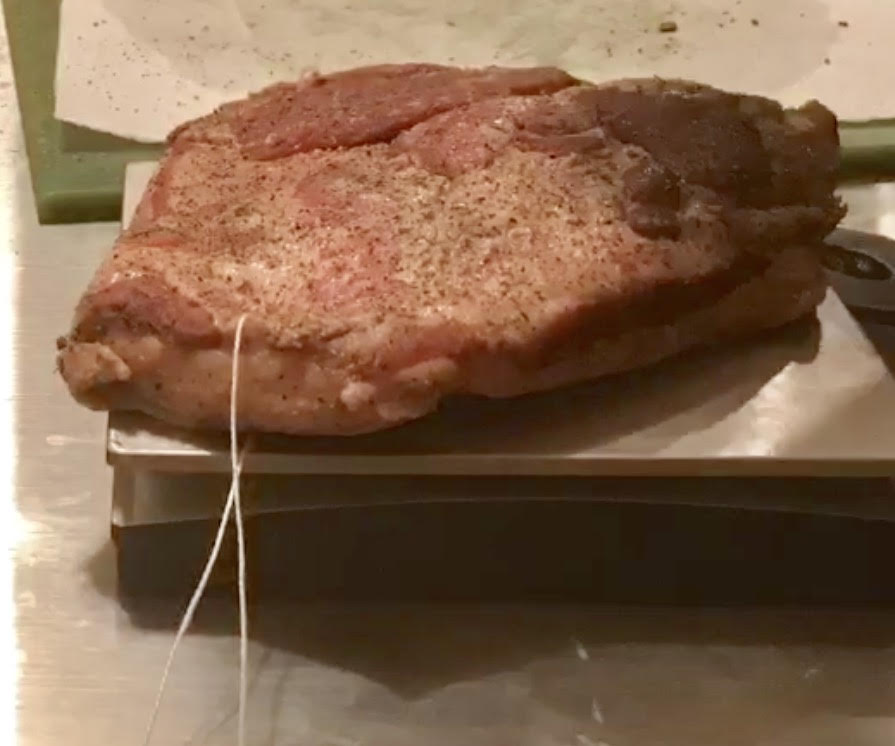

Once you have weighed all of your ingredients, you can put them aside while you deal with the meat. First, you want to cube the meat into smaller chunks that will fit in your grinder. I par-freeze my meat, and keep it in the freezer while I am working to ensure that it stays cold and therefore grinds more easily. After the meat is cut, I mix it with the spice cure that I previously had measured out. Some people wait until the meat is ground to mix in the spices, which is also an option, but I feel as though I get a better mixing process achieved by mixing them before grinding (however, it makes my grinder a lot messier this way).

Grinding and Stuffing Phase:

After the meat and spices are mixed, I ran it through the grinder on a fine grind. After the meat was ground, I mixed it in a stand mixer on a low speed to promote adhesion. Then I added the mixture to my vertical stuffer and stuffed the meat into hog middles, a traditional casing for ‘nduja.

Fermentation Phase:

~70F/80-90%RH (starter culture dependent)

After stuffing, I allowed the meat to ferment for 48 hours in my fermentation chamber (aka my oven with the light on, a pan of water at the bottom, and the occasional water spray bottle service).

Cold Smoking Phase:

After the fermentation stage was done (and boy was I glad when this time was up, hog middles stink like no other casing I have worked with before), I put the meat into my cold smoking set up, and cold smoked them with beech wood for 4+ hours.

Drying Phase:

~55F/70%RH

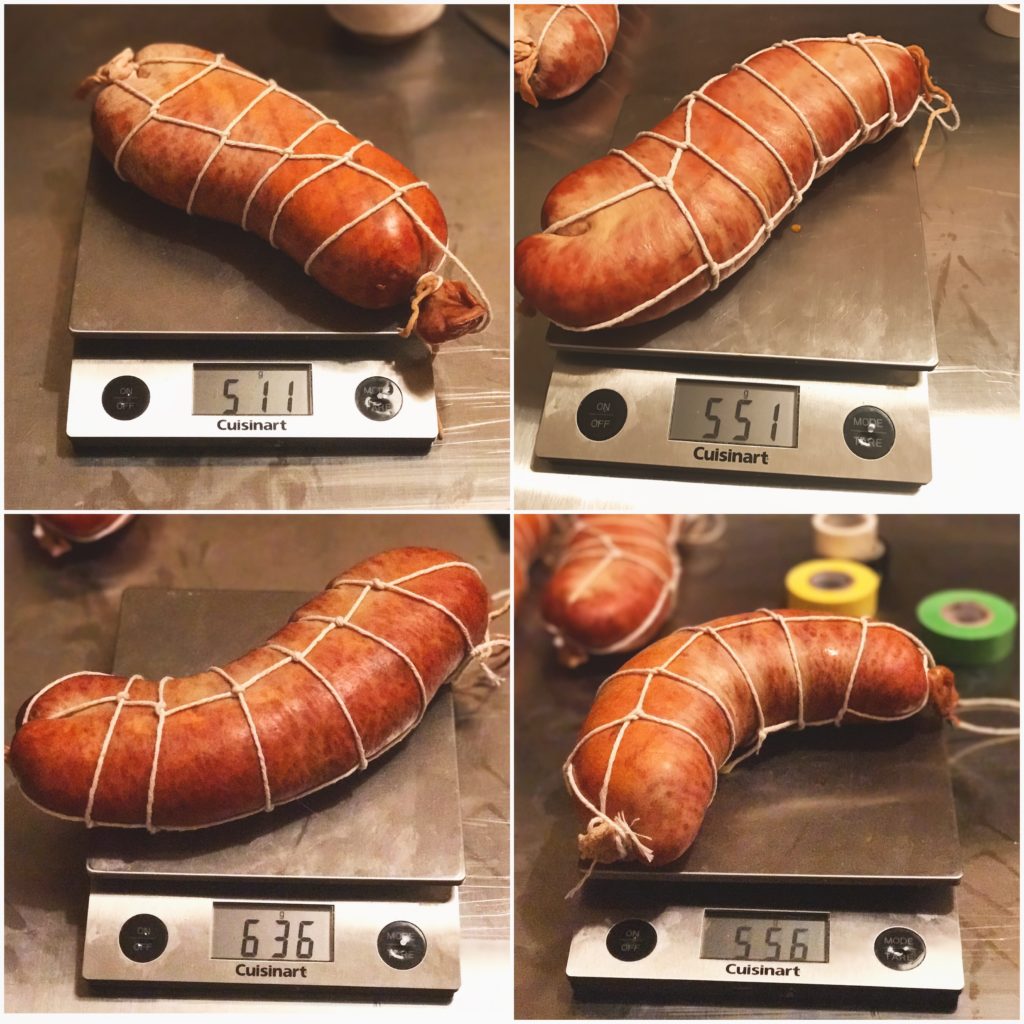

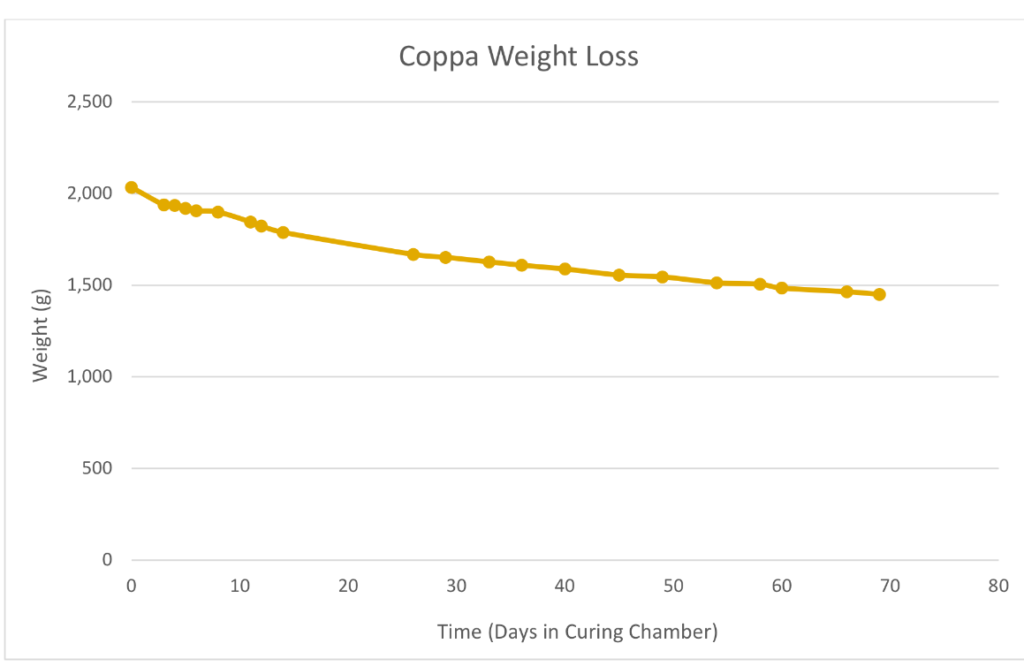

After cold smoking, I tied and weighed each of them.

Then I hung them up in the curing chamber to dry.

‘Nduja has such a high fat content that it’s not expected to lose much weight in the drying phase (10-20%), but importantly it experiences a maturation of flavor in this time. Most people hang their ‘nduja by time instead of weight loss for this reason, and I picked a time point of 2 months.

Tasting Phase:

After 2 months, my ‘nduja had each lost about 20% of their initial weight, more than I expected.

I cut it open and was excited by how beautiful it looked. So, I dove right in. I took a knife and spread some onto a nice piece of toasted sourdough.

WOW. I was blown away; an instant favorite. I knew that I had better start a second batch immediately, because I was going to find a way to sneak this into every dish I made, as well as eat it as a snack as often as possible.

It’s a great way to start a sauce for pasta.

Really, just great all around.

Disclaimer: Meat curing is a hobby that comes with inherent risks. We can all do things to limit this risk by educating ourselves about the process and the utilizing the safest known methods to create our products. This website is for educational purposes only, and all experimentation should be done at each individuals own risk.