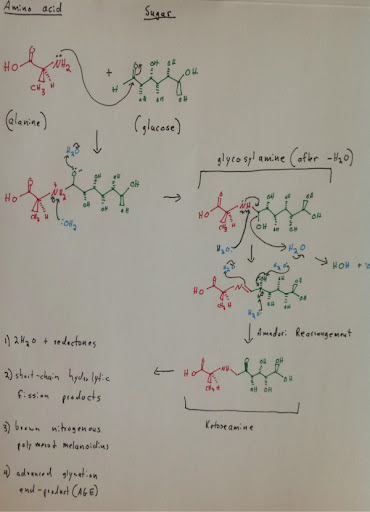

Maillard reactions are responsible for creating some of the most delicious flavors in cooking. Maillard reactions are referred to as “browning reactions”, as they are responsible for the taste of items such as toasted bread or seared steak. A Maillard reaction is a chemical reaction that occurs between what is referred to as a reducing sugar and an amino acid. An example of a reducing sugar is glucose. An amino acid can be found at the end of a peptide chain, in say meat. (Maillard Wikipedia)

This is illustrated well by many of the projects done by Breadventures_NJ (http://www.breadventuresnj.com/), such as the following pretzel puffs:

Maillard Wikipedia: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maillard_reaction

Amadori Wikipedia: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amadori_rearrangement

Kitchen as Laboratory: The Kitchen as Laboratory: Reflections on the Science of Food and Cooking, Edited by Cesar Vega, Job Ubbink, and Erik van der Linden

Cooking for Geeks: http://www.cookingforgeeks.com/

On Food And Cooking: The Science and Lore of the Kitchen (Google eBook) by Harold McGee

Breadventures_NJ: http://www.breadventuresnj.com/

Leave a Reply