Ratings of the Best Non-Pork Fat Options for Salami:

- Brisket (cow) Fat: Best option, low melting point, palatable taste

- Duck Fat: Second best option, harder to work with due to room temperature melting point, great taste

- Lamb/Goat/Cow Fat: Easy to access, may have strong flavor, higher melting point

- Fat Replacer: Fine for increasing fat mouth feel, no chunks of fat, doesn’t really cut it

- Lamb tail fat: Hard to find, personally have never used, seems promising

Overview:

Most salami that we see in the stores and restaurants today are made out of pork meat and fat. Even salami that are made from different animal meat sources often use pork fat due to its beneficial properties. It has a great flavor and a lower slip melting point (the way that the melting point of a waxy solid, such as a fat, is measured and reported) than most other animal fat, although not so low that it becomes a liquid on the lower end of room temperature. This means it maintains its integrity when in the salami, but will melt in your mouth when you take a bite. Basically, creating perfection.

However, some people choose not to eat pork. Having friends and family who are pork free, I have done a lot of research into finding pork free charcuterie recipes. For the most part, this hasn’t been too hard. There are many pork free whole muscle cure alternatives. When I turned my attention to salami though, I faced a conundrum. Most recipes that use non-pork meat still use pork fat because of its aforementioned qualities. I found historical evidence of halal salami producers using lamb tail fat, but it is notoriously difficult to find in most areas of the United States. Some stores sell “fat replacer” to help with the mouth feel that fat produces, but is not the same as having real chunks of fat in your salami.As a pork eater myself, I cannot deny the pleasure of pork fat, as it melts in your mouth, creating sinful bliss. I was determined to find a way to replicate this so that my non-pork eating friends could enjoy the same luxury as me.

As a side note, I discuss these fat options in terms of salami because that is what I have focused on making. It can also apply to sausage and other charcuterie products.

Background:

As a chemist by training, my initial instinct where to look into the chemical composition of the fat of different animals compared to pork. The slip melting point will vary based on the ratio of different fatty acids in the fat itself, therefore it is important to know what types of fatty acids each fat you are considering uses has, and in what ratios.

There are saturated and unsaturated fatty acids. Saturated fatty acids tend to “stack” better together, and are therefore are harder to “pull apart”, and tend to have a higher melting point. Unsaturated fatty acids have double bonds which introduce a kink into the molecule. This means they cannot stack as well, are easier to “pull apart”, and therefore have a lower melting point.

Stearic Acid is an example of a saturated fatty acid:

Oleic Acid is an example of an unsaturated fatty acid:

As you can probably see from their structure, saturated fats like stearic acid have no problem stacking together. This makes them harder to pull apart, as discussed above. Whereas, from the structure of oleic acid, you can see that there are kinks on the molecular structure that make it less stackable, and therefore make it easier to pull apart. (These terms are not 100% scientifically accurate but are being used to illustrate the concept, feel free to read the source material for a more scientific discussion of the forces that hold these molecules together.)

In general, animal fats have a slip melting point between 22-40 C/71-104 F. It turns out, the ratio of unsaturated to saturated fatty acids plays a very important role in creating these slip melting points.

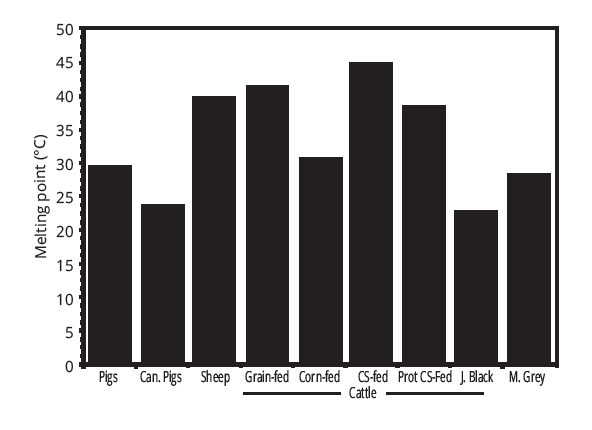

The composition of the fats from different animals varies based on their species, their diet, their genetics, and the area that the fat is taken from. These are all important factors that one must consider when looking at fat sources. For example, some animals are purposely fed a particular feed in order to lower their fat slip melting point. Other animals have been engineered to have increased marbling with lower slip melting points of that fat.

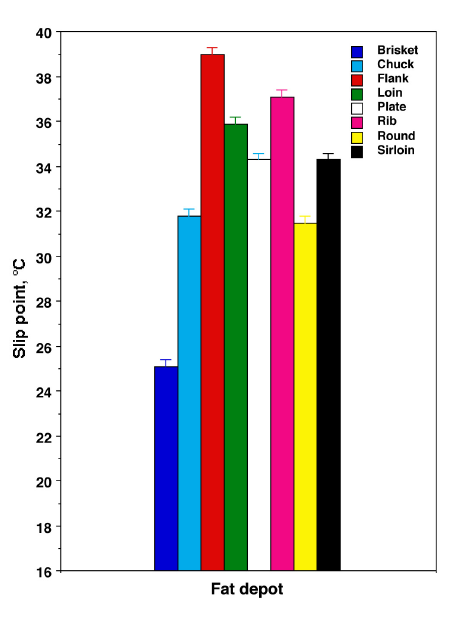

So, what does this have to do with our quest for a non-pork fat source for salami? A lot, actually. In general, pig fat tends to have a slip melting point around 30C, which varies based on feed, genetics, and cut. Cow fat, the most commonly available substitute, has an average slip melting point of 40C. This difference is enough to change that melt in your mouth feel that well cured pork products succeed in producing.

Brisket (cow) Fat:

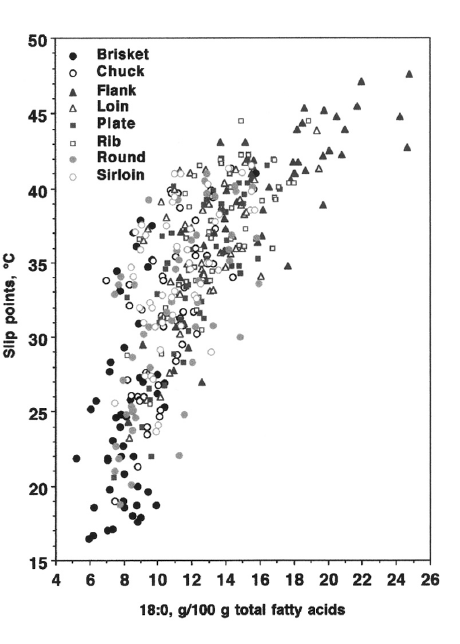

Interestingly, fat from the brisket cut of a cow has a very unique composition. It is high in unsaturated fats like oleic acid, and low in saturated fats like stearic acid. This means that the fat from the brisket area of a cow has a much lower melting point than cow fat in general; in fact it averages around 25 C. This is a slip melting point as low as most pork fat, making brisket fat an ideal substitute for pork fat.

The data shows that the fat from areas that have lower concentrations of saturated fats have a lower slip melting points. Brisket fat has fewer saturated fatty acids, and therefore a lower slip melting point, as illustrated in the following figure:

The data shows that the fat from areas that have lower concentrations of saturated fats have a lower slip melting points. Brisket fat has fewer saturated fatty acids, and therefore a lower slip melting point, as illustrated in the following figure:

Since the way that animals are raised, their genetics, and their feed play such an important role in the overall taste of the fat, I would love to see more research looking at these factors as well. One example of ongoing research is the genetic engineering of Japanese black cattle (think Waygu or Kobe beef) which have been engineered to have higher ratios of unsaturated fatty acids, better marbling, and a lower slip melting point. In addition, the distinctive taste of jamón iberico de bellota fat is created by a combination of genetics, European acorn feed, and the way the pigs are raised. Farmers in the United States (and abroad I am sure as well) are doing a lot to understand how important these factors are for their pigs, and are doing really good work ensuring that they raise pigs that not only have higher ratios of unsaturated fatty acids but great marbling and taste. All of these factors are important in creating delicious cured meat products.

Overall, there is some really interesting research being done on this topic, and for those who are scientifically minded I suggest taking a look into the literature. In the references below (where the figures have come from), I have referenced two pamphlets that have been written for the general public consumption, which I have found very fascinating. They have their own references page, where more information on individual studies can be found.

Duck Fat:

Duck fat is my second recommendation for fat to use in salami. It is a particularly palatable fat, but does have a slip melting point that is around room temperature, some sources saying that it is around 77F/25 C. This can make working with it tricky. However, as long as you keep your temperatures low and work fast, there is no reason it can’t be used. In addition, if you are working with an old world culture, many suggest a lower fermentation temperature anyway. I found that using a fermentation temperature of 75F/23-24C worked perfectly for duck fat salami.

I should mention here, that by duck fat, I mean actual fat that has been taken off of a duck, not rendered duck fat like you can buy at the supermarket. Rendered duck fat does not have the collagenous matrix that raw duck fat from the animal has, and won’t hold up nearly as well in salami making. I will be posting the recipe of an all duck salami that I have made with duck fat, in order to give more insight into how this process can go smoothly and create a delicious final product.

Lamb/Goat/Cow Fat:

I assume that if you are making non-pork salami, you probably have a piece of meat that has both non-pork meat and fat. Using this fat is my third favorite option. The benefits are that the fat is on hand already. With this method, you make sure that nothing goes to waste.

One aspect of using this fat, which may be a benefit or a drawback (depending on your opinion) is that fat tends to store a lot of the flavor of the animal. Adding lamb or goat fat may add a stronger flavor to the salami than desired. Then again, that may be the exact desired outcome.

The big downside is the texture. The slip melting point of most commercially available animals, in most cuts, will be higher. This means the salami will not “melt in your mouth” in the same way as a pork salami will. However, talk to farmers, see how they treat and feed their animals. You may be able to find animals that have fat that is more amenable to your uses. Just because something commercially available may not be perfect, doesn’t mean the right option isn’t out there if you do your research and talk to the right people.

Fat Replacer:

Fat replacer is a commercially available product that is added to salami to create the mouth feel of fat without actual fat. It is made of cellulose, xanthum, and konjac. All of these are used to “mimic” the texture of fat. There are claims that it is good for “healthy” salami. I personally doubt any health claims the company may make, but if you are trying to make a pork free (or even vegetarian) salami and want to use this as a substitute, it’s not awful. That being said, I would use it in conjunction with actual fat as mentioned above.

Lamb Tail Fat:

The elusive lamb tail fat. As discussed above, many factors play a role in the slip melting point of fat. Of particular importance are the genetics of the animal, its feed, and the area you are taking the fat from. This is especially true for lamb tail fat. While most lamb have thin tails these days, certain breeds have fat tails. The fat in these tails, due to physiological reasons, has a lower slip melting point. As discussed above in the case of brisket cow fat, this creates that “melt in the mouth” taste that is so appealing.

I cannot say too much more about this, since I have never used it myself. I would love to try it in the future however. It seems to be used in many traditional halal products, so if you can get your hands on it and try it, I would imagine that it would be worth it.

People who know way more about lamb tail fat than me have written blog posts on it that are worth reading:

http://www.jennifermclagan.com/fat-tailed-lamb

http://www.anissas.com/those-fat-tails/

Summary:

All in all, these are some good non-pork alternatives to fat for salami or sausage making. I did some research, stumbled upon some things, and tried them out. This is by no means an extensive list, nor will it work for everyone. I suggest everyone to do as much research as they can and come to their own conclusions. I welcome any feedback from people who make non pork salami and any methods they have found to be useful.

References:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stearic_acid

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oleic_acid