Capocollo ibérico de bellota. Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes. My previous post on making capocollo used a bit of a fancier cure. Here I had such a fantastic piece of ibérico de bellota meat that I used as simple a cure as possible.

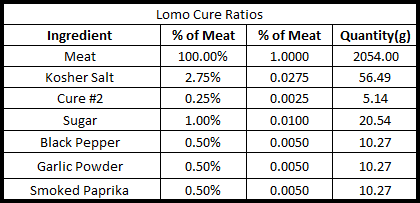

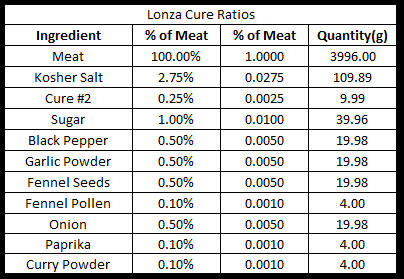

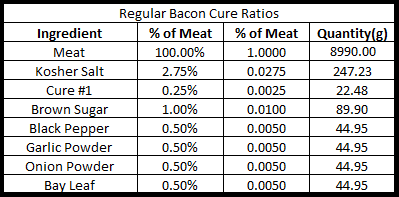

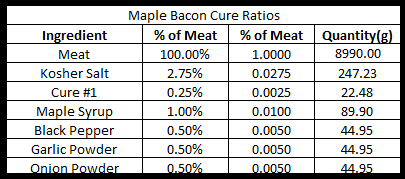

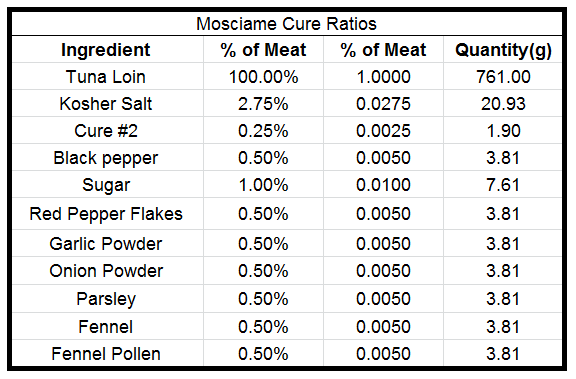

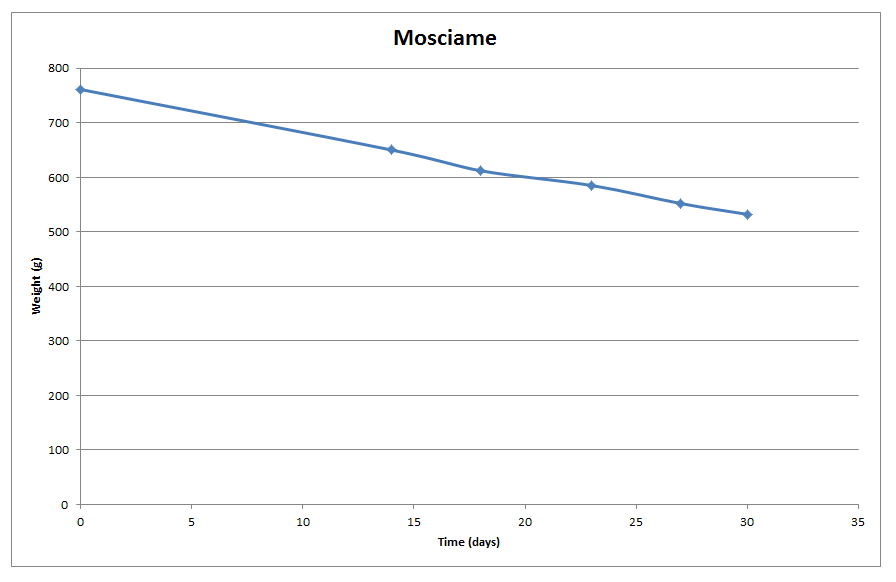

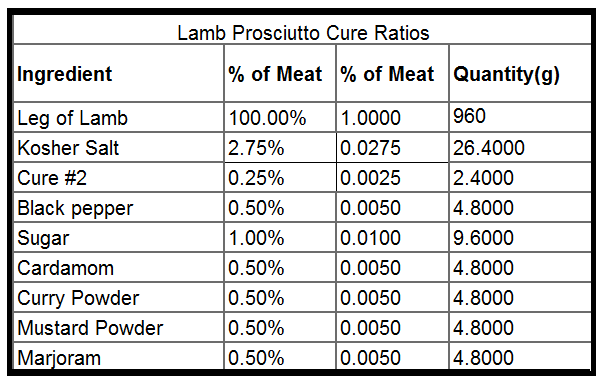

Curing (2 weeks+): I weighed the meat for this project, and calculated the simple cure that would be used.

The meat was allowed to stay in the cure for at least 2 weeks. In this case, it stayed in a few months because I got busy, one of the benefits of using an equilibrium cure.

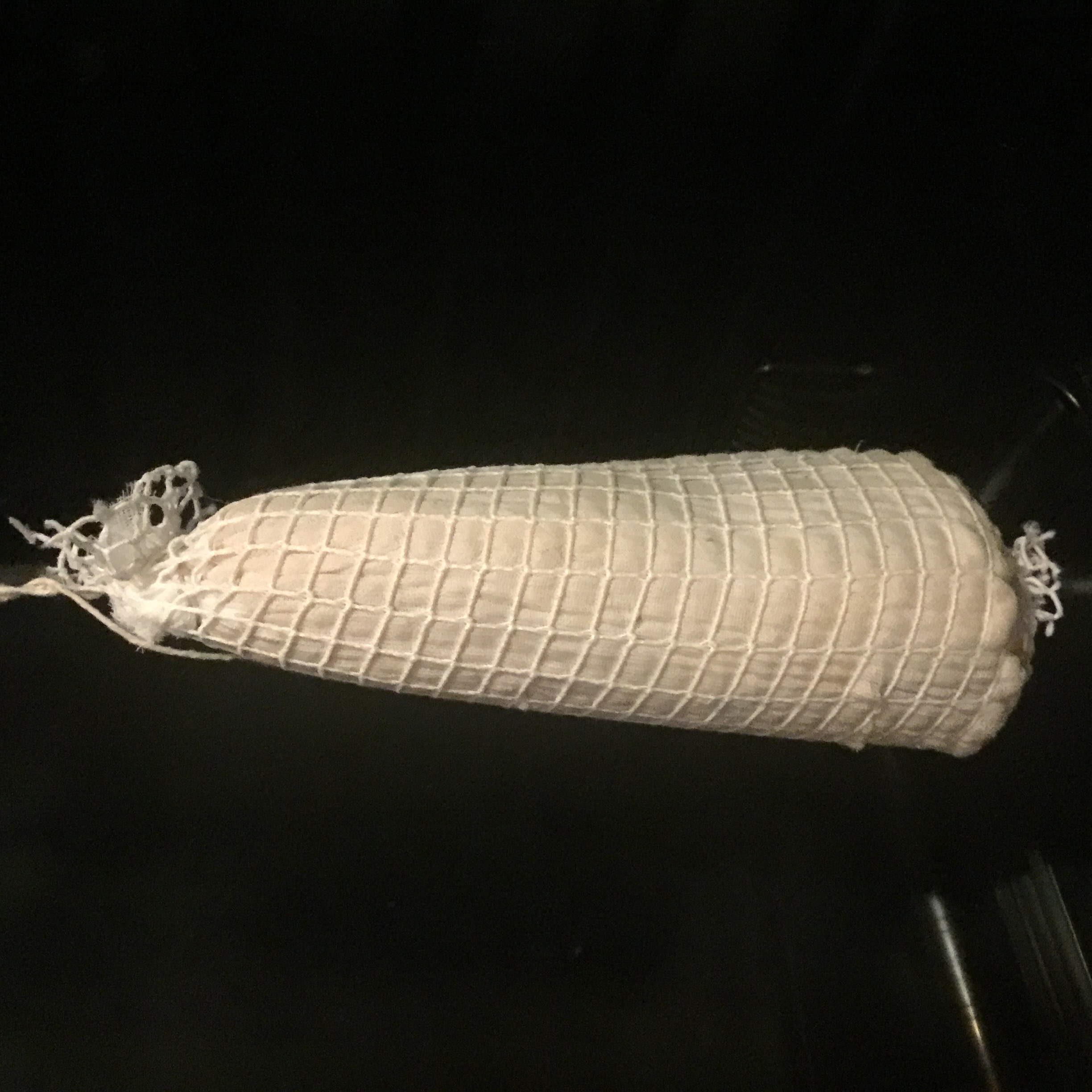

Casing (1 hour+): The meat was taken out of the cure, rinsed and patted dry, cased in a beef bung, and netted.

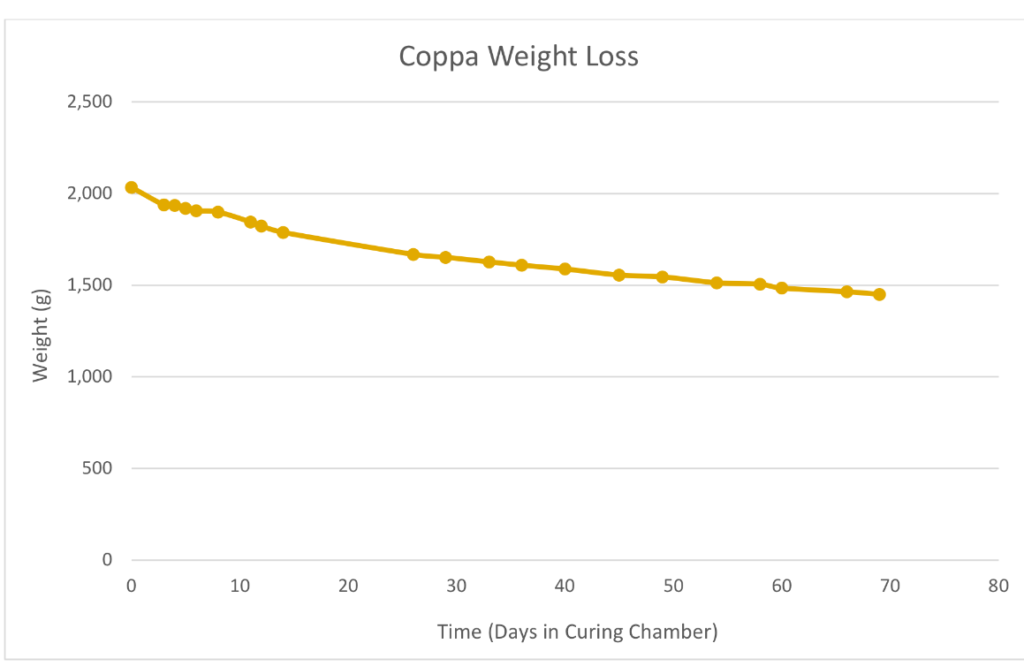

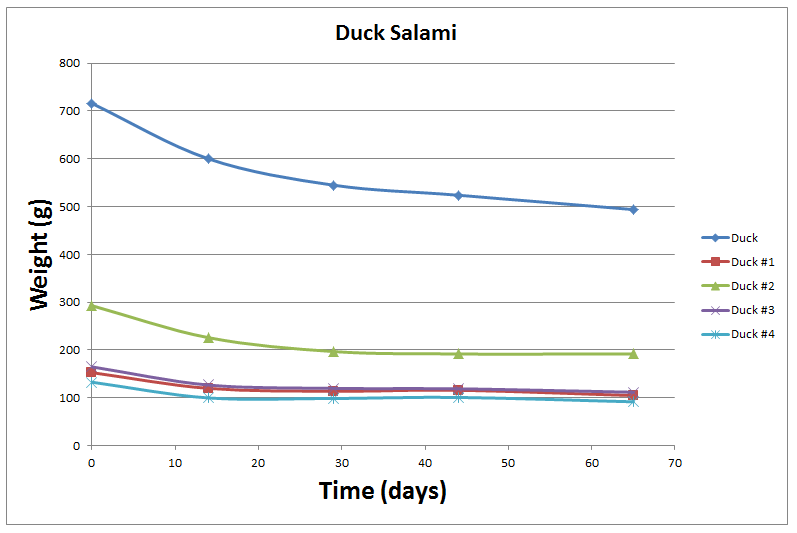

Drying (3 months+): This meat was allowed to hang until it lost 30% of its weight.

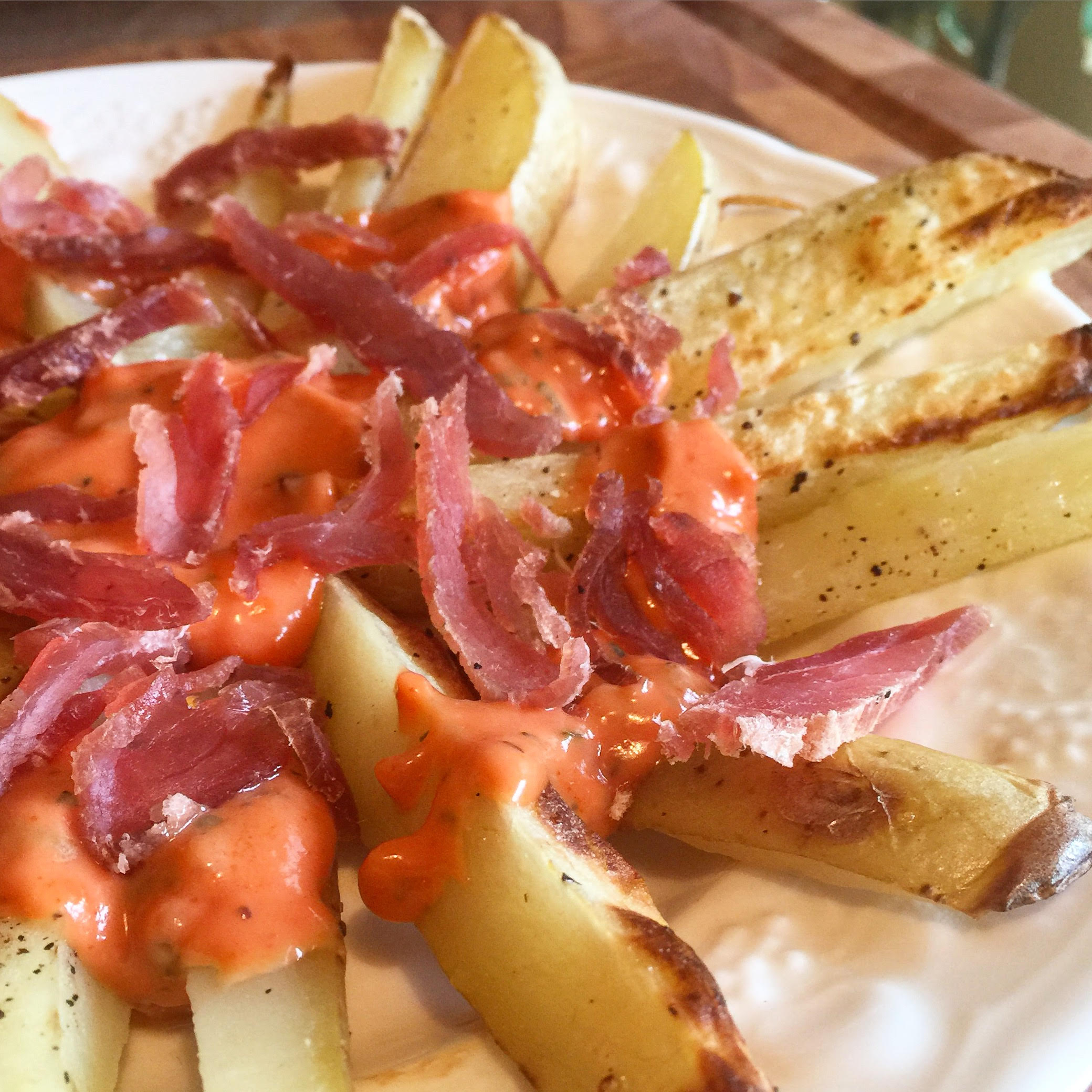

Tasting: WOW. This was a fantastic piece of meat, with just basic prompting from me, it turned into a fantastic cured meat. This is a winner. I will be doing this one again.

Perfect to slice up and serve as a snack.

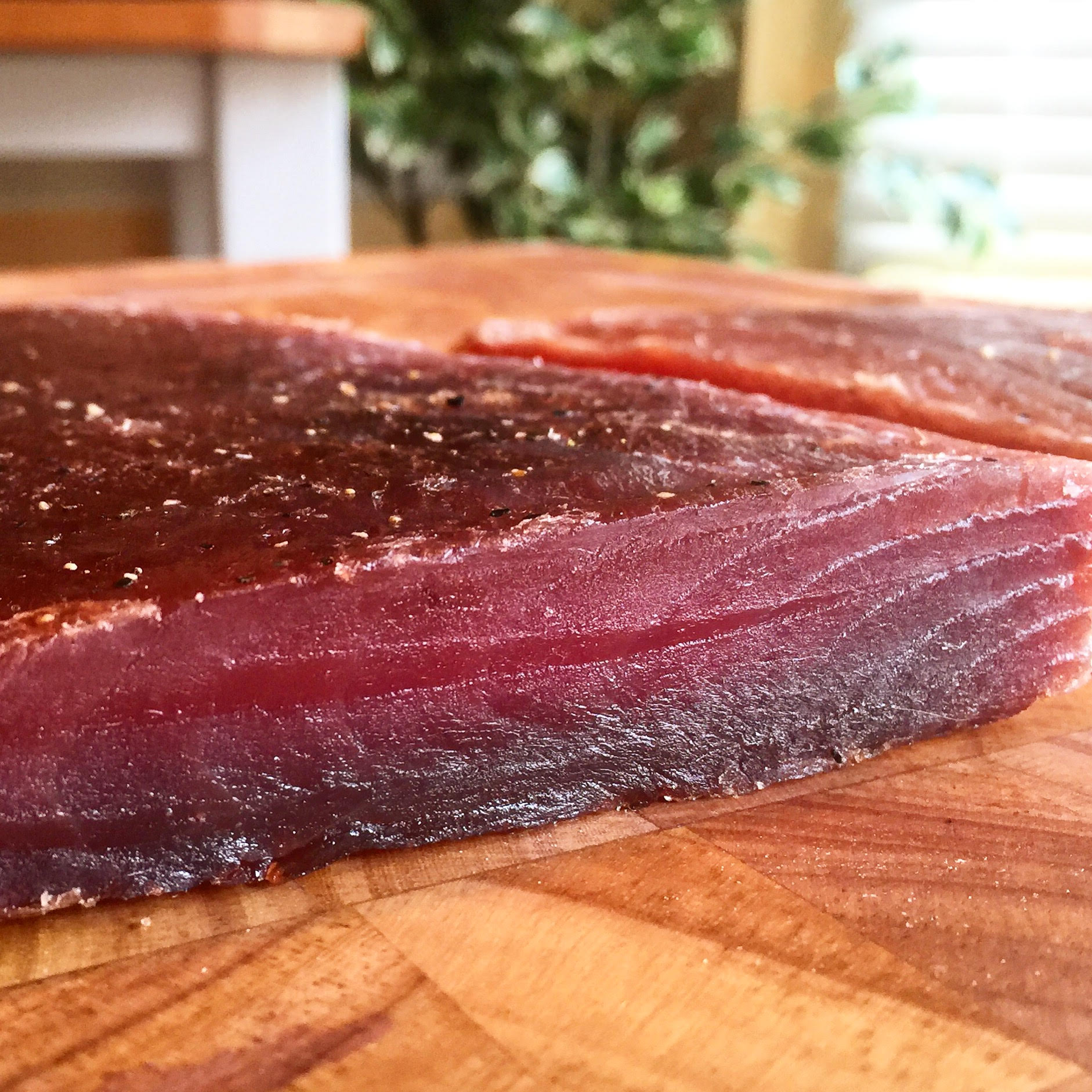

That’s some beautiful meat right there.

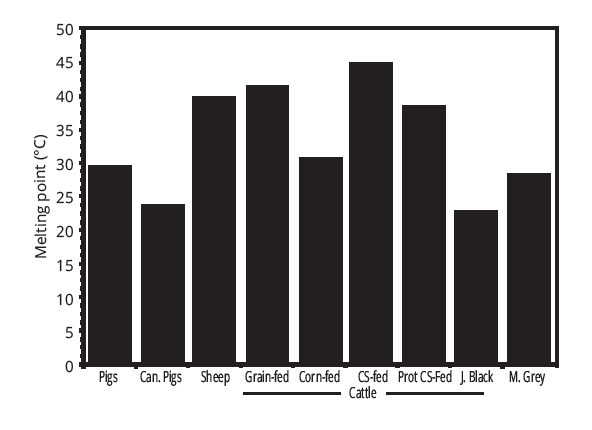

Love to see that great fat.

Disclaimer: Meat curing is a hobby that comes with inherent risks. We can all do things to limit this risk by educating ourselves about the process and the utilizing the safest known methods to create our products. This website is for educational purposes only, and all experimentation should be done at each individuals own risk.