Coppa. Capocollo. Gabagool. I love how cured meats have so many different and interesting names. The general idea here is that the muscle that runs along the neck of the pork shoulder is dry cured. This cured meat product is generally called Coppa in northern Italy, and cured in a more northern manner with spices particular to the region. Capocollo is the name in southern Italy, and since “Capo” means the head in Italian, and “collo” means the neck, you can see that the name is descriptor of where the muscle lies. Personally, I find the history of the name gabagool to be the most fascinating. Called gabagool by Italian-Americans, primarily in the state of New Jersey, this is a very cool regionalism. The majority of the immigrants who came to America and settled in New Jersey were from southern Italy and Sicily. Italy has a number of regional dialects/languages, and in the south, there is a pattern of dropping of the last vowel in words and the pronunciation of “c” as “g” (see this fantastic article for more details: http://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/how-capicola-became-gabagool-the-italian-new-jersey-accent-explained). With these linguistic changes, capocollo becomes gabagool. Just because these names are all different, doesn’t mean that any of them are wrong per se, just regional variations.

Curing (2 weeks+):

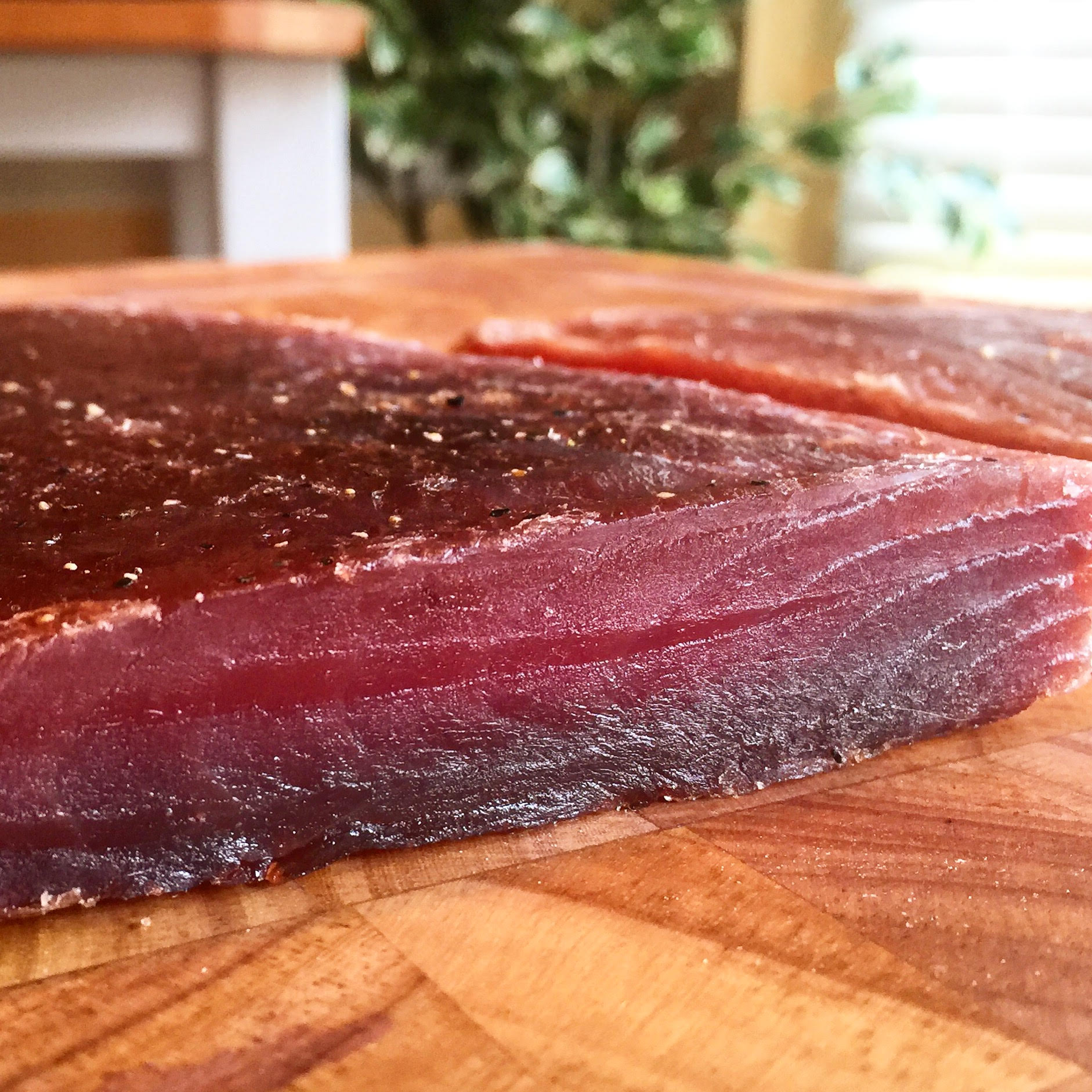

First, you will need to harvest the coppa from the shoulder, or have it butchered for you. In this post, I will be using a beautiful piece of meat from a Mangalitsa pig. These are an Old World breed pig that are indigenous to Hungary. They are well known for the quality and quantity of fat that they have, which makes them a perfect breed to use in meat curing.

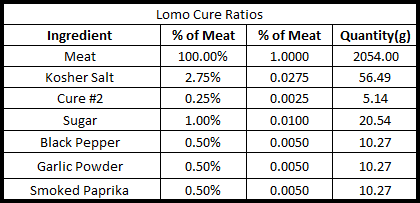

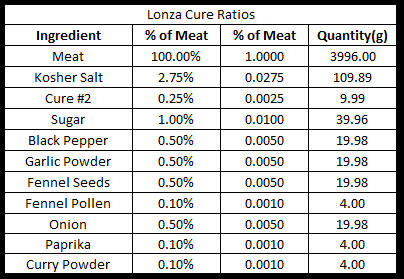

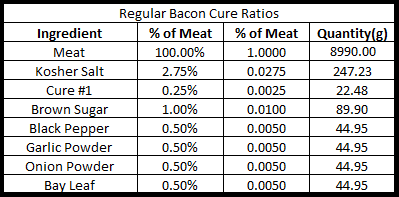

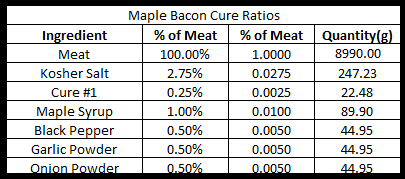

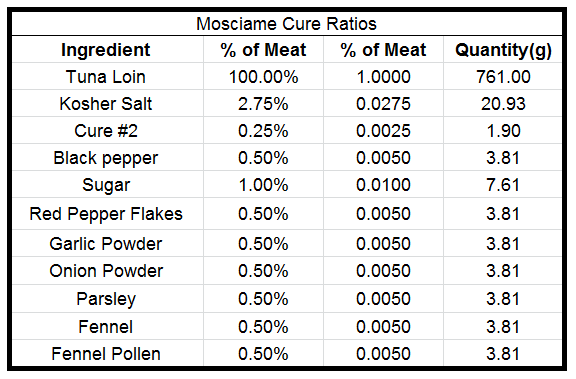

First, I weighed the meat and put the value into my curing spreadsheet.

All of the cure ingredients were weighed.

They were then mixed, and spread onto the meat.

The meat was vacuum sealed with the cure ingredients and allowed to cure in the fridge for 2 weeks.

Casing (1 hour+):

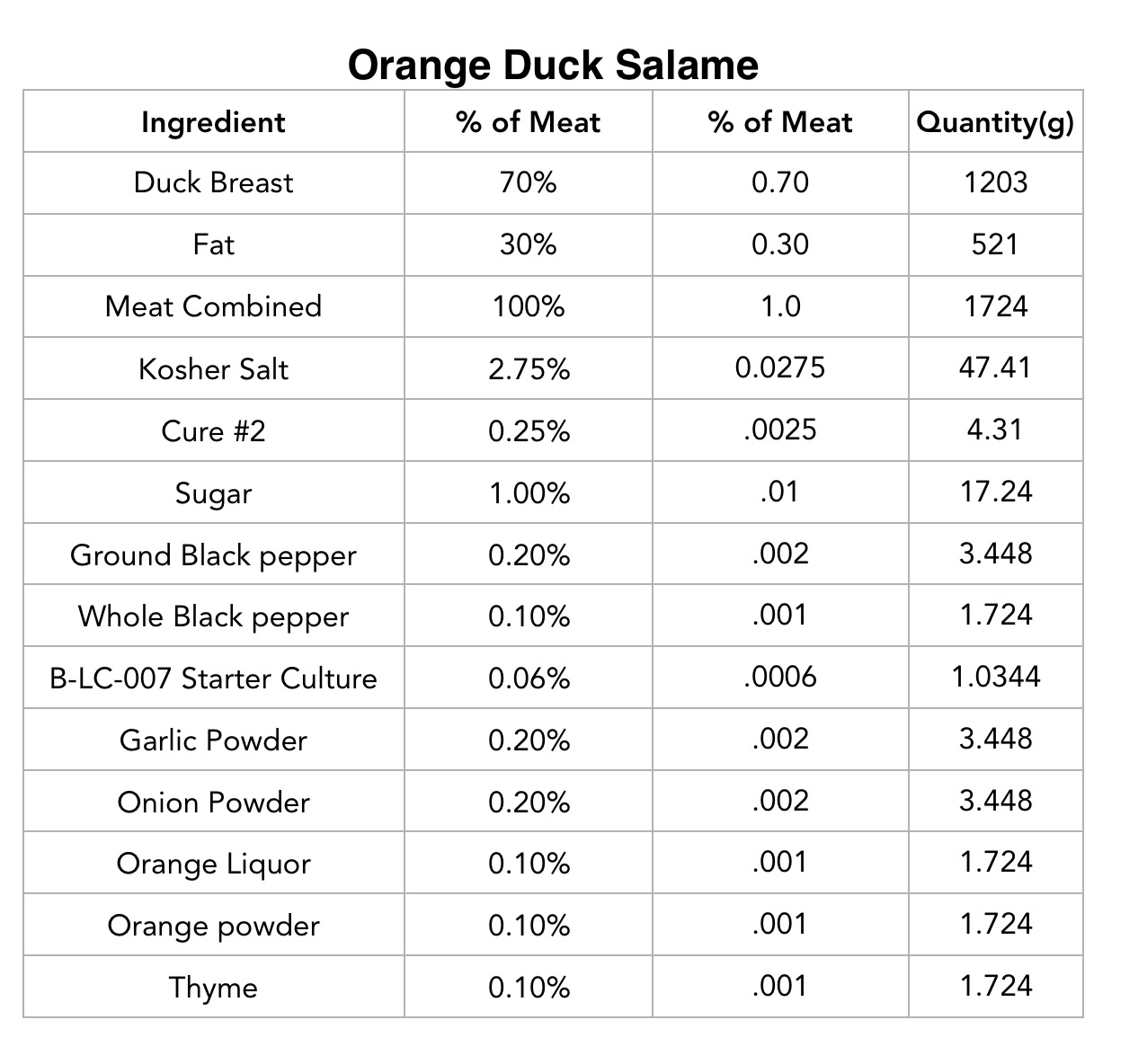

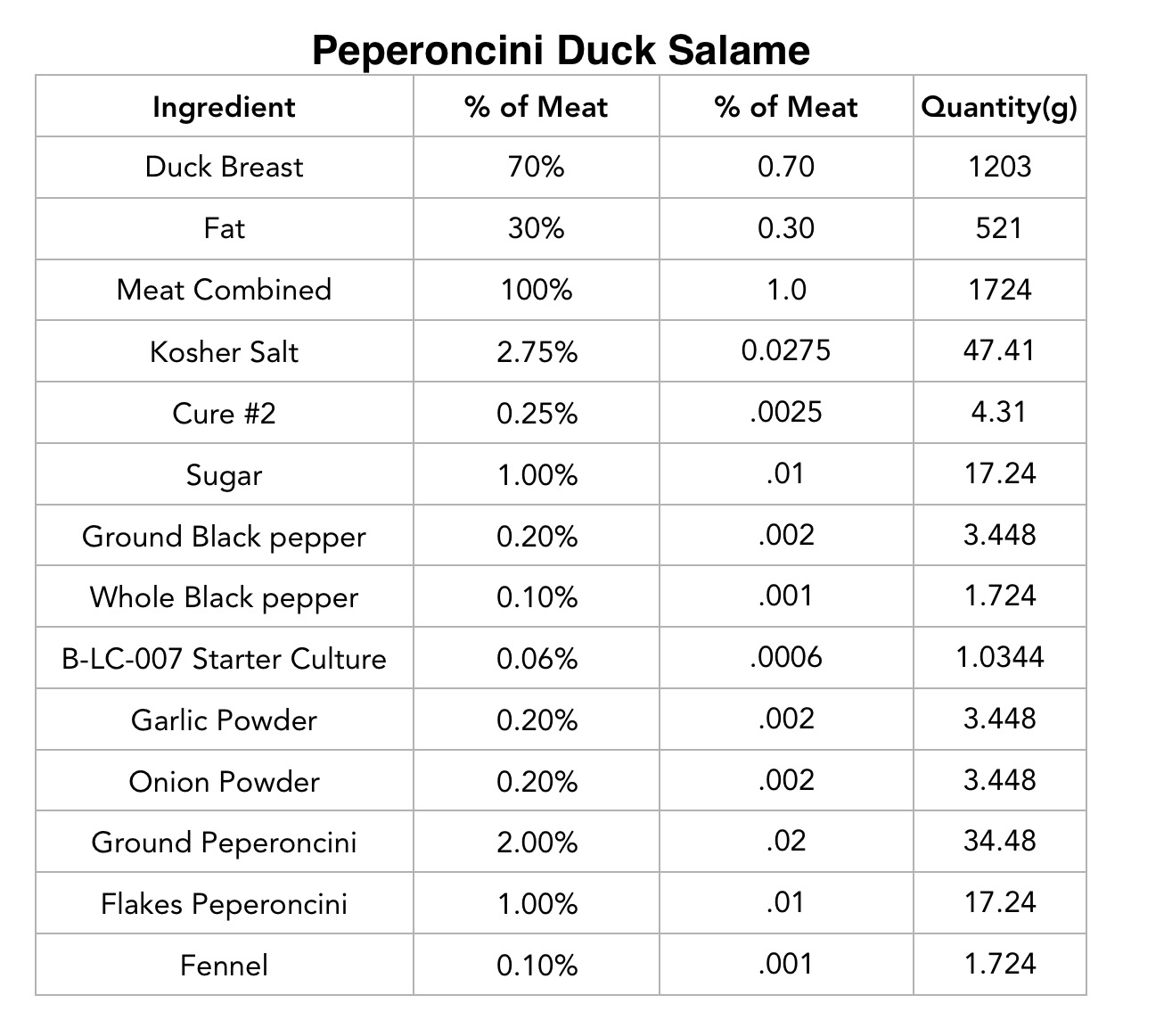

After sitting in the cure for 2 weeks, the meat was rinsed off and patted dry. For this meat, I wanted to leave a coating of toasted fennel and peperoncini around the outside. I mixed these together in a bowl first.

Then, I coated the meat with the spices.

I cased this in a beef bung. In order to do this, I soaked the beef bung in warm water for about an hour before I started.

Then I slowly stuffed the meat into the beef bung casing.

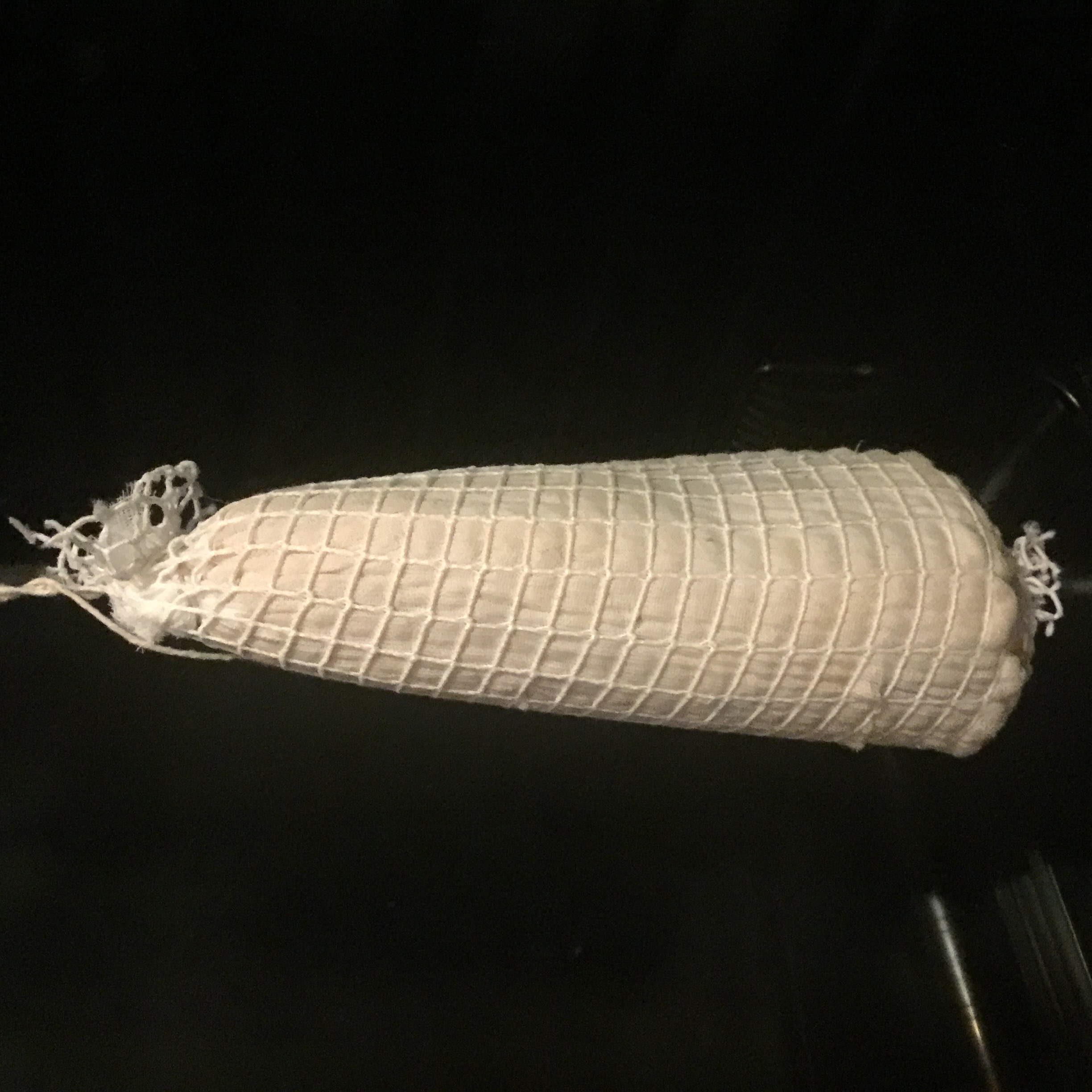

This was finally netted and weighed.

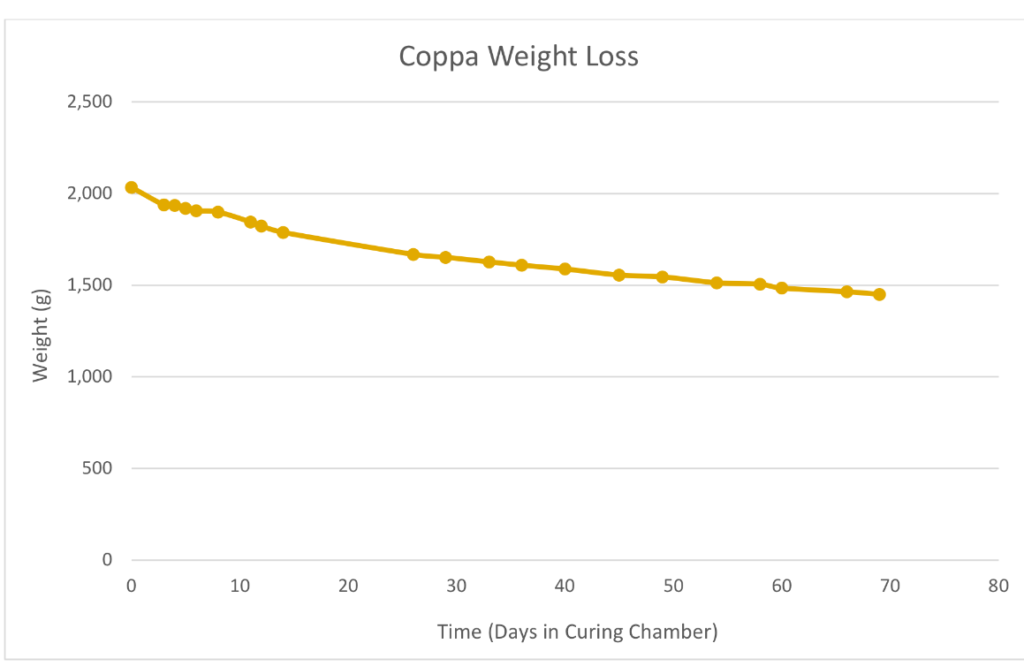

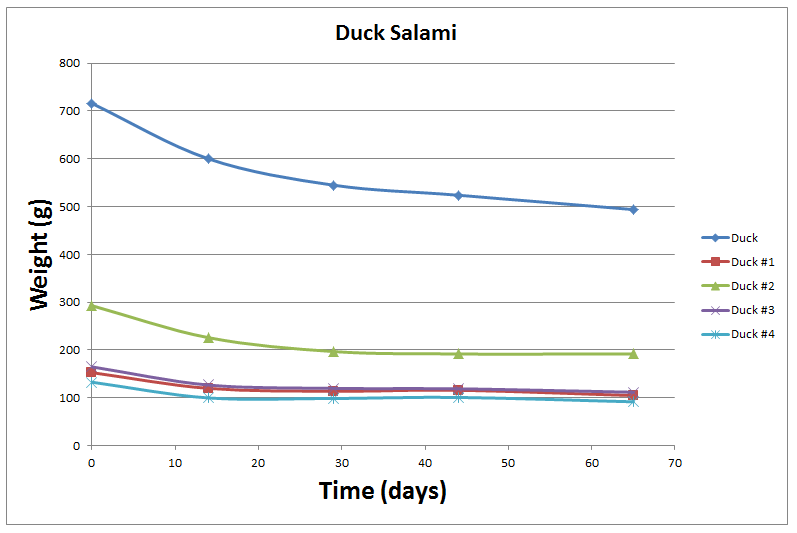

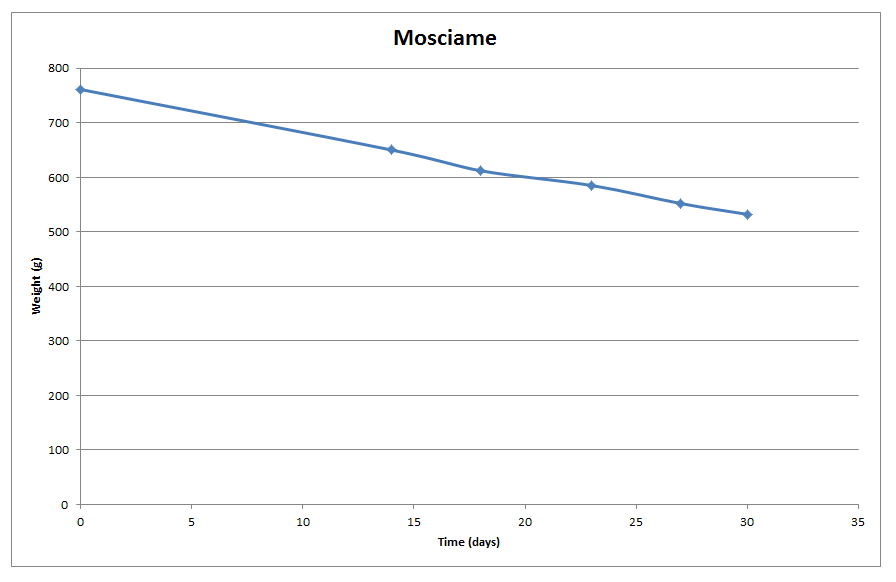

Drying (3 months+): The meat was allowed to hang in the curing chamber for 3 months, and the weight loss was tracked over time.

Over time, there was increased beneficial mold growth and weight loss, avoiding areas with high concentration of peperoncini.

At around 3 months, it reached 30% weight loss, and was pulled from the chamber.

—

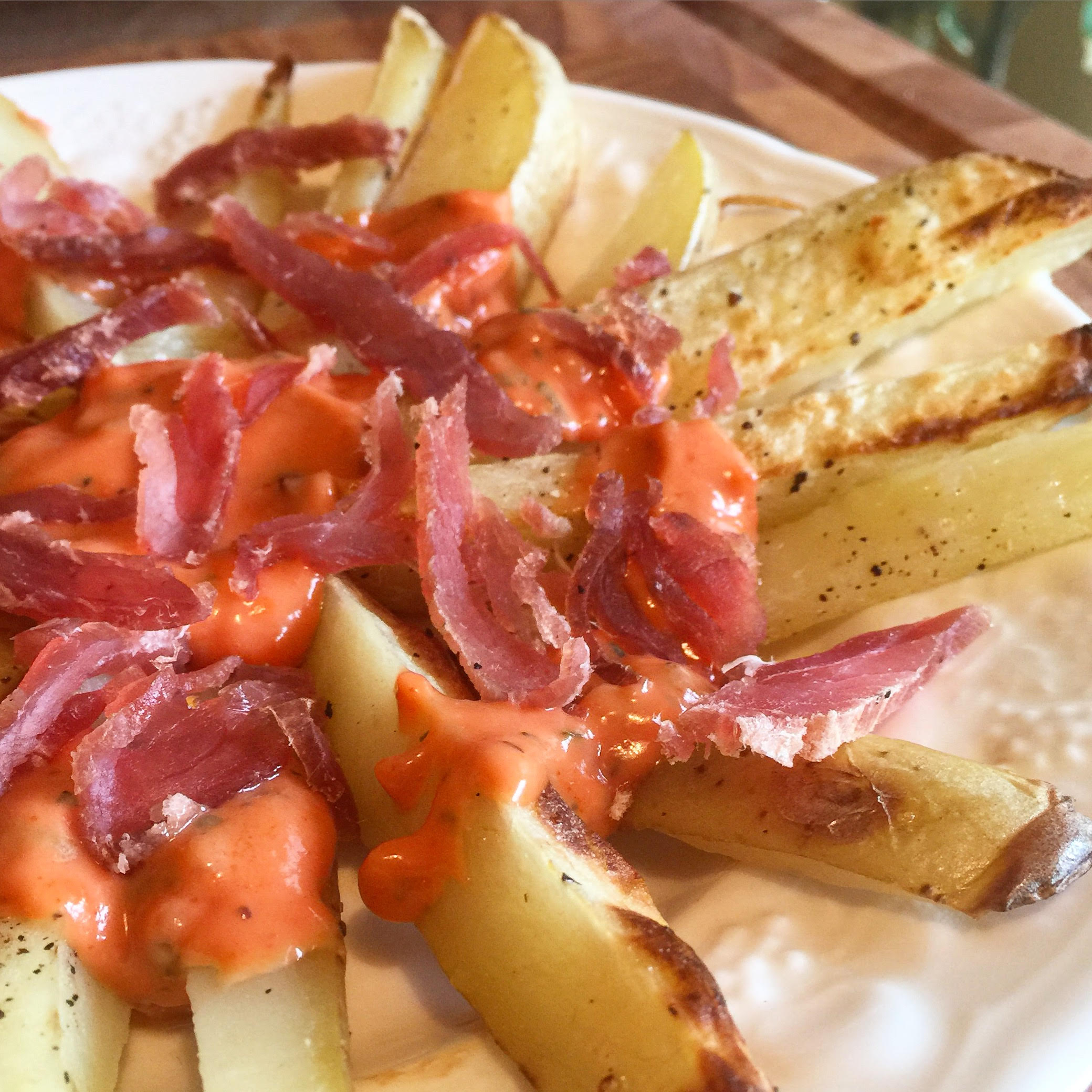

Tasting: When this meat was sliced it looked beautiful! The flavor was a bit over powering at first, but after it was allowed to equalize in the fridge under vacuum seal for a few more months, it was outstanding!

Disclaimer: Meat curing is a hobby that comes with inherent risks. We can all do things to limit this risk by educating ourselves about the process and the utilizing the safest known methods to create our products. This website is for educational purposes only, and all experimentation should be done at each individuals own risk.