Have you ever tried a raw olive off of an olive tree? It makes me wonder how anyone ever unlocked the key to these bitter fruits. In the Mediterranean region in particular, olive trees abound. One taste of a raw olive directly off the tree would be enough to set anyone off the fruit entirely. However, at some point in history, it was discovered that it was possible to use salt and brine solutions to store the olive harvest as well as to leach away the bitter compounds, oleuropeins. And so, our love affair with olives and olive oil began.

In the beginning of the season, olives are green. As they spend more time on the tree, they darken and become black. Both green and black olives can be cured.

I have been interested in curing my own olives for a while now, but geographically, I don’t have access to olive trees. This year, I placed an order with a farm in California, and received 17 lbs of black olives.

I decided to cure the majority using a brine method, and the rest using a dry salt cured method.

Methods: In this post, I will be discussing the dry salt cured method of preserving olives.

First, you have the raw black olives. You want to sort them for deformities, and wash the pile of good olives, and dry them off.

After you have sorted the good olives from the bad olives, weigh the olives that you have. Mix the olives to salt in a 2:1 ratio (aka for 2 lbs for olives, mix in 1 lb of salt). Mix them thoroughly.

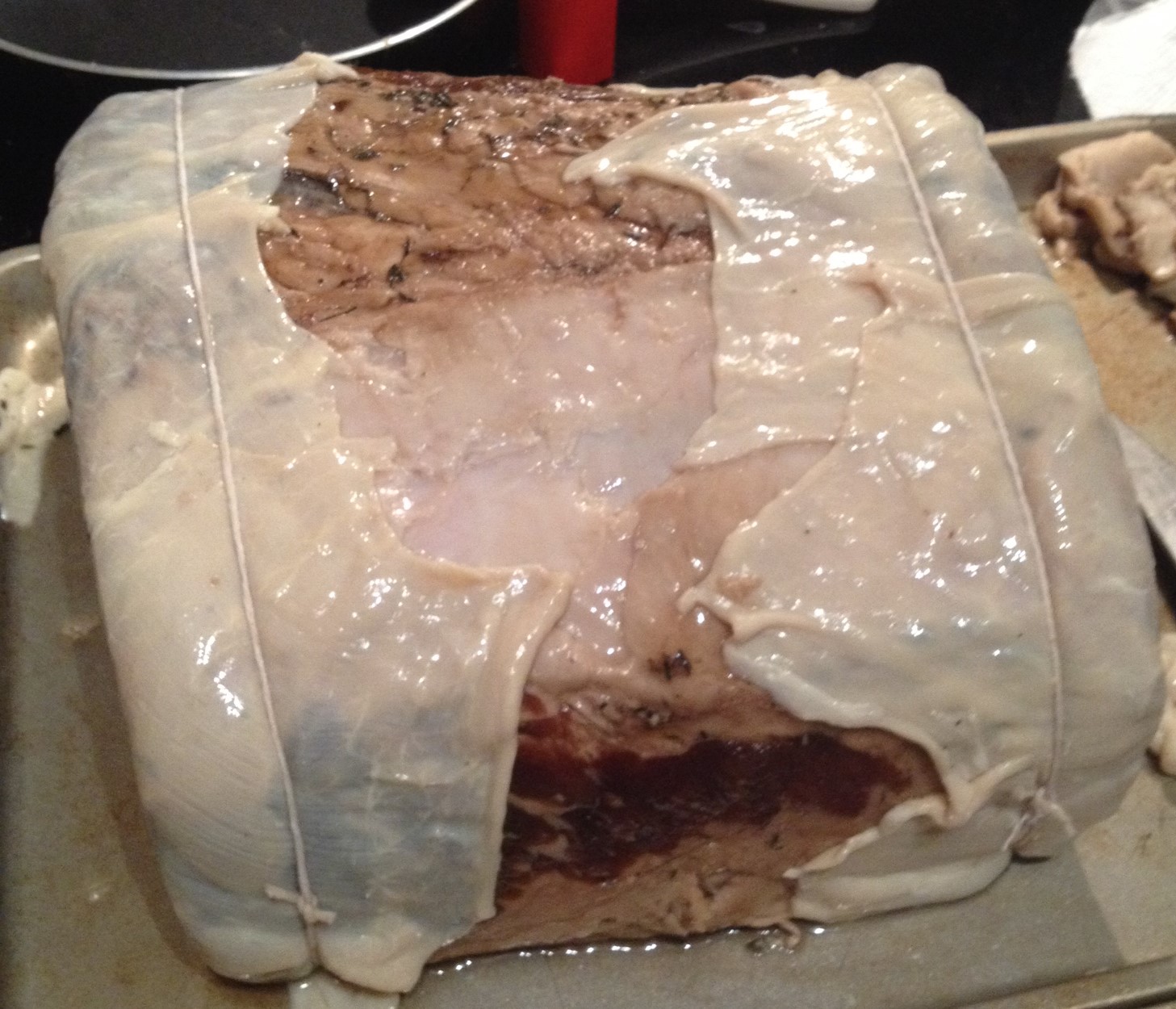

Next, you want to set up a container to hold the salt and olives for the next 6-8 weeks at room temperature (60-80 F). I used a cheese mold lined in cheesecloth that worked out well.

Pour the olives into the container, cover with a new layer of salt, and lay the tails of the cheesecloth over the olive and salt mixture.

Once a week, re-mix this mixture by pouring the olives and salt into another container, mixing it around, and pouring it back into the cheesecloth lined cheese mold.

After 6-8 weeks, the olives are most likely ready.

Pour the olives out over a sieve to get rid of the extra salt, and allow them to dry overnight.

To store the olives: Make a 10:1 ratio of olives to salt (aka 10 lbs of olives to 1 lb of salt). Mix this together, and store in an airtight container at room temperature (use within 1 month), in the refrigerator (use within 6 months), or in the freezer (use within 12 months).

I stored mine in a mason jar that I sealed using a vacuum sealer, and they are now safely stored in the fridge.

To eat the olives: Take the olives out of storage, and boil them for a few minutes (optional step). Allow them to air dry, and soak them in olive oil with herbs. I have found that they are best if they are allowed to marinate in the olive oil and herbs at least overnight if not longer.

Resources:

http://anrcatalog.ucanr.edu/pdf/8267.pdf