“And if you don’t know, now you know.” -The Notorious B.I.G.

Culatello and Fiocco di Prosciutto (…plus the Rumpetto)

While most people like prosciutto, only those who really know, know of and enjoy culatello. Culatello is often referred to as the heart of the Prosciutto. It is created when you take the freshly cut rear leg of a pig and you remove the leg bones from it. In doing this, you create two whole muscle bundles of meat. The larger of these is the prized culatello di prosciutto while the smaller of the two is the fiocco di prosciutto, often passed off as the ugly step sibling of the culatello, but quite wrongly so. The culatello, while made from the same part of the pig as the prosciutto, has a much different flavor; earthy and sweet, a delicate balance of fat and meat that dissolves on your tongue.

The Meat

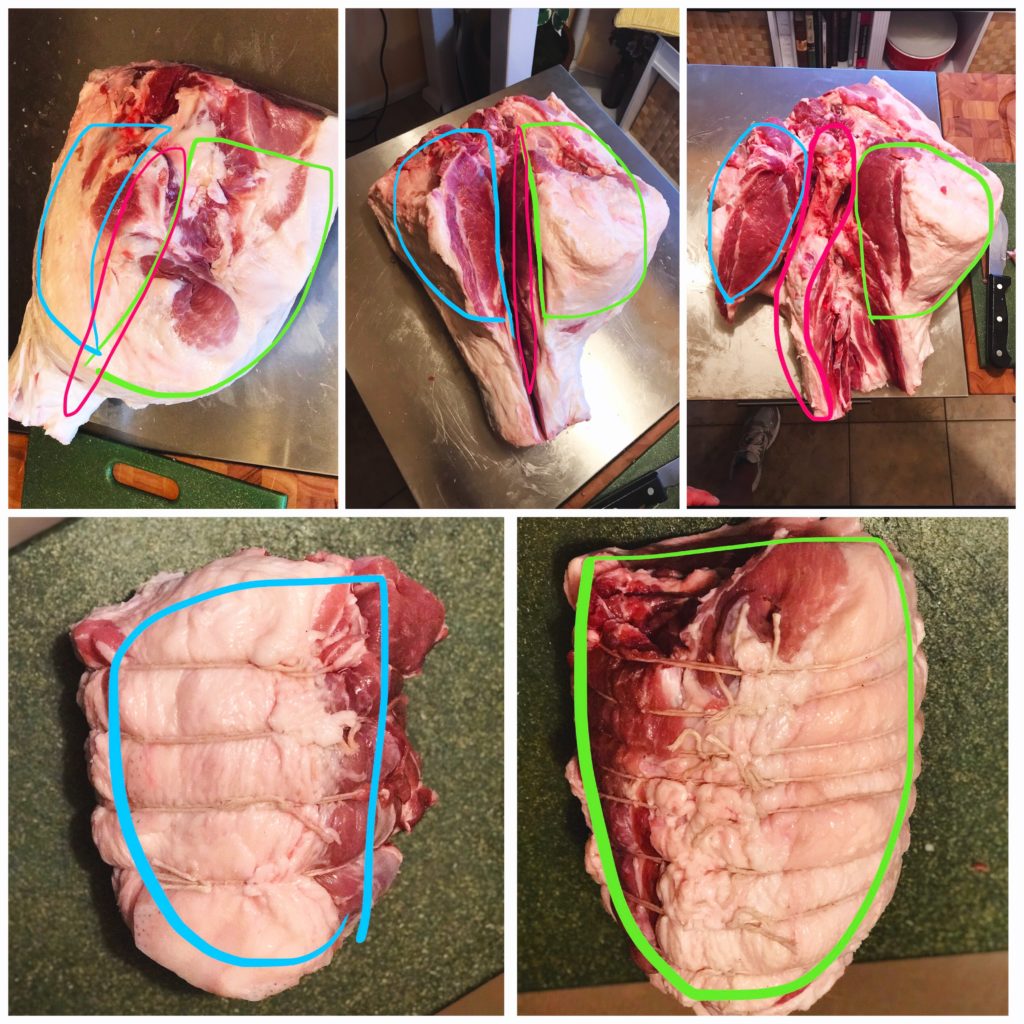

In order to butcher out the culatello and fiocco, you are going to need to understand a bit of the anatomy of the rear leg. Usually, you will receive a leg primal with part of the hip bone still attached. At the face of the meat, the hip bone articulates with the proximal end of the femur. The femur bone runs through the upper portion of the pig rear leg, the distal end of which articulates with the tibia and the patella to form the knee joint. Then, the tibia and the fibula run through the lower portion of the leg. It’s important to understand how these bones lie in the meat, in order to understand how we will need to remove them to get at the culatello and fiocco cleanly.

Once you have situated yourself, the first step is to skin the leg. You can either do this now, or wait until you have removed the aitch bone. Either way is fine. Do this carefully, making sure to leave on as much fat as possible. I’m still working on my skinning skills, so it takes me some time and effort to do this, but experts can do this in a few quick knife strokes.

Next, you want to remove the portion of the hip bone that articulates with the proximal end of the femur, commonly referred to as the aitch bone. You want to gently remove the aitch bone from the head of the femur, cutting any connective tissue between the two that you come across. This will become easier with practice, as you familiarize yourself with the shape of the bone and the way it protrudes into the meat. It is important to do this carefully, and not cut unnecessarily into the meat. Feel free to use your hands to feel around the bone and inform your cuts. Free the aitch bone entirely, and remove it from the leg.

When the aitch bone is removed from the leg, it should have as little meat on it as possible, meaning that your cuts were clean and efficient. Mine is not quite there, but with practice, makes perfect.

After you have removed the aitch bone, you should have what looks like an Italian style prosciutto leg, with the exposed ball joint at the face of the meat.

Similarly to making a prosciutto, what you want to do at this point is start to milk the femoral vein. After death, blood can pool in the venous system, even if the blood was drained during the slaughtering process. We want to eliminate all the blood from this piece of meat before we start curing, or it could negatively impact our end results. There are a number of videos and descriptions online of how to do this, but briefly, I attempt to trace the femoral vein through its course in the leg, starting at the distal end and working my way to the proximal face. I apply as much pressure as possible, and attempt to force blood out of the vein in this manner. It’s also important to note, this isn’t a process you can do only once. If you receive a leg that has been frozen, sometimes the blood will be frozen as well, and won’t drain on the day you are cutting. Its important to do this multiple times throughout the process, to make sure all the blood is really drained.

Finally, it’s time to do the thing that, if you’re experienced making prosciutto, seems sacrilegious; cutting into the leg. There are traditional ways to do this, but I’ve found a method that I prefer and that works for me. I prefer to cut straight down on top of the bone, and carefully extract it. As someone with less experience, this method helps me to make sure that I don’t commit any grievous errors. If you are more experienced, you can simply “know” where the bone runs, and cut the culatello off by feel.

Once I have exposed the bone and freed it from its attachments to the bundles of meat that are the culatello and fiocco, you have a few options for how you want to cut them out. I like this method, because by leaving both the culatello and fiocco attached, you gain a triangular shaped whole muscle at the face of the prosciutto.

I like to make the first cut across the leg, to trim up the faces of the culatello and fiocco, while simultaneously freeing this meat that I call the rumpetto. I like to cure this with spices and cold smoke it, in a modified version of speck. If you don’t save this muscle whole, you can use this extra meat for salami.

Once the face of the meat is trimmed, you can cut out the entire culatello and fiocco.

You want to trim the culatello into its characteristic teardrop shape. Once you have trimmed it up, you want to tie it using tight slip knots, to help it maintain its shape and make sure there are no air pockets created during the butchering process. And that’s it! You’ve shaped your culatello and fiocco.

Salting (4C/40F, 3 weeks+)

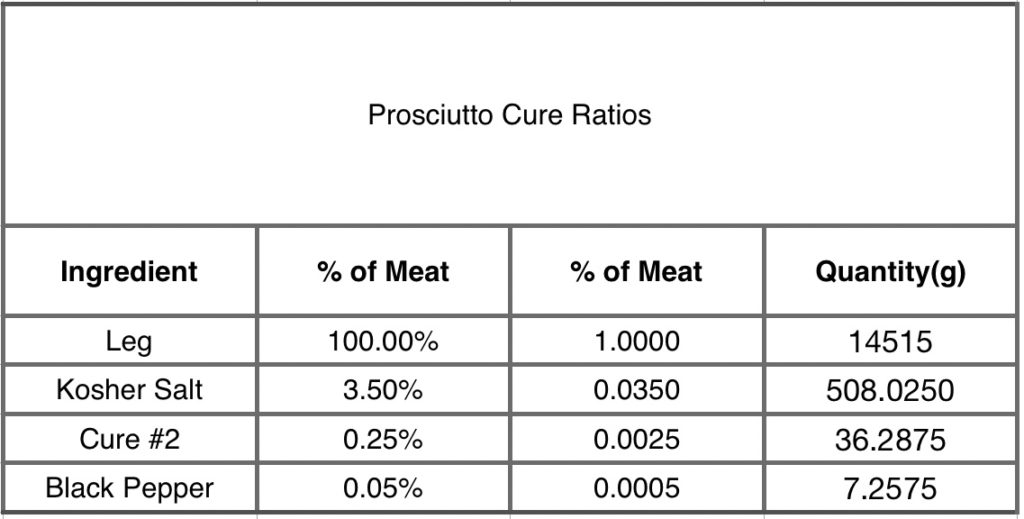

For the salting of culatello, I like to keep it simple. I do an equilibrium cure with salt, black pepper, and cure #2. Some people don’t use cure #2 for whole muscles like this, but I do. I generally cure both the culatello and fiocco in this simple cure, although sometimes I will experiment a bit with the fiocco. I keep them curing in a vacuum sealed bag in the fridge. You can use the following interactive spreadsheets to calculate the cure you will need for your own project; just fill in the weight of your meat in the appropriate white cell in the spreadsheet and hit enter. There is no need to make any other changes to the spreadsheet.

For the rumpetto, I used an alpine spice mix generally used for making speck.

*Notes:

1- Please use common sense. Make sure the spreadsheet is working properly for you and double check any calculations that don’t seem right.

2- I like to use equilibrium curing. It allows me some flexibility in when I process the meat after curing, since the time left in the cure doesn’t matter, it is the percentages that are used that do. However, some people don’t do this type of curing and use excess curing instead. In excess curing, it is the time that the meat is left in the cure that matters. If you would rather do excess curing for culatello, cure the culatello in excess sea salt for 1 day per kg of meat. (For example, for a prosciutto that weights 14 kg, this means it would stay in excess sea salt for 14 days).

Casing

Once the culatello and fiocco have been allowed to cure for the appropriate amount of time, you need to rinse them and case them. The culatello is traditionally cased in a hog bladder, since it is one of the few things that will expand to the necessary size. Depending on where you live, you may be able to find hog bladders for sale online. I like the ones that have been packed in salt, not the ones that have been pre-dried that you need to rehydrate. However, it’s really whatever works for you.

You will need to soak the bladder first, to allow it to relax and expand.

When you’re ready to go, you cut open the mouth of the bladder, and stuff the rinsed and dried culatello inside. It may seem like it won’t fit, but chances are it will. Once its in, you need to sew the bladder back to together. You can do this using any type of needle and thread that works, or even surgical sutures! I treat the fiocco the same way as the culatello, so by the end I have two pieces of meat encased in bladders.

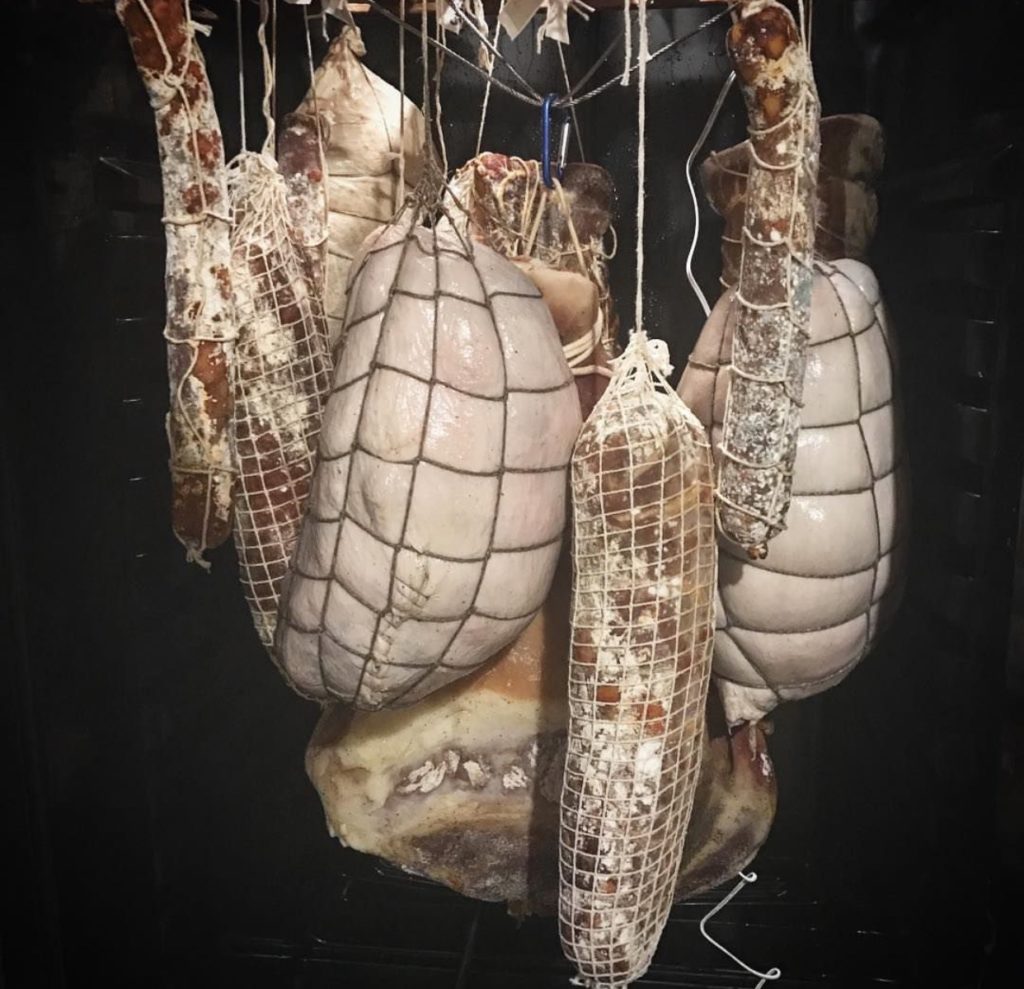

Once the meat is cased in the bladder, it’s time to tie it. Experts can do this process in the matter of 10 minutes or less. The rest of us can be happy just to have it done. It’s hard to explain the tying of the culatello, because you really need to watch it being done. There are a number of videos online for it, so I suggest searching google for videos on how to do the tying. The traditional culatello di Zibello type of tying is what we’re going for here. Of course, at this point the tying is mostly aesthetic, but it’s nice to learn the tradition and can actually be quite fun.

On the other hand, the rumpetto was easily cased in a beef bung, and was hand tied more simply. After tying, it was cold smoked for 4 hours using beechwood.

Drying (13C/55F, 70%RH, 9-12 months):

After you have tied your culatello, fiocco, and rumpetto, you are ready to let them hang.

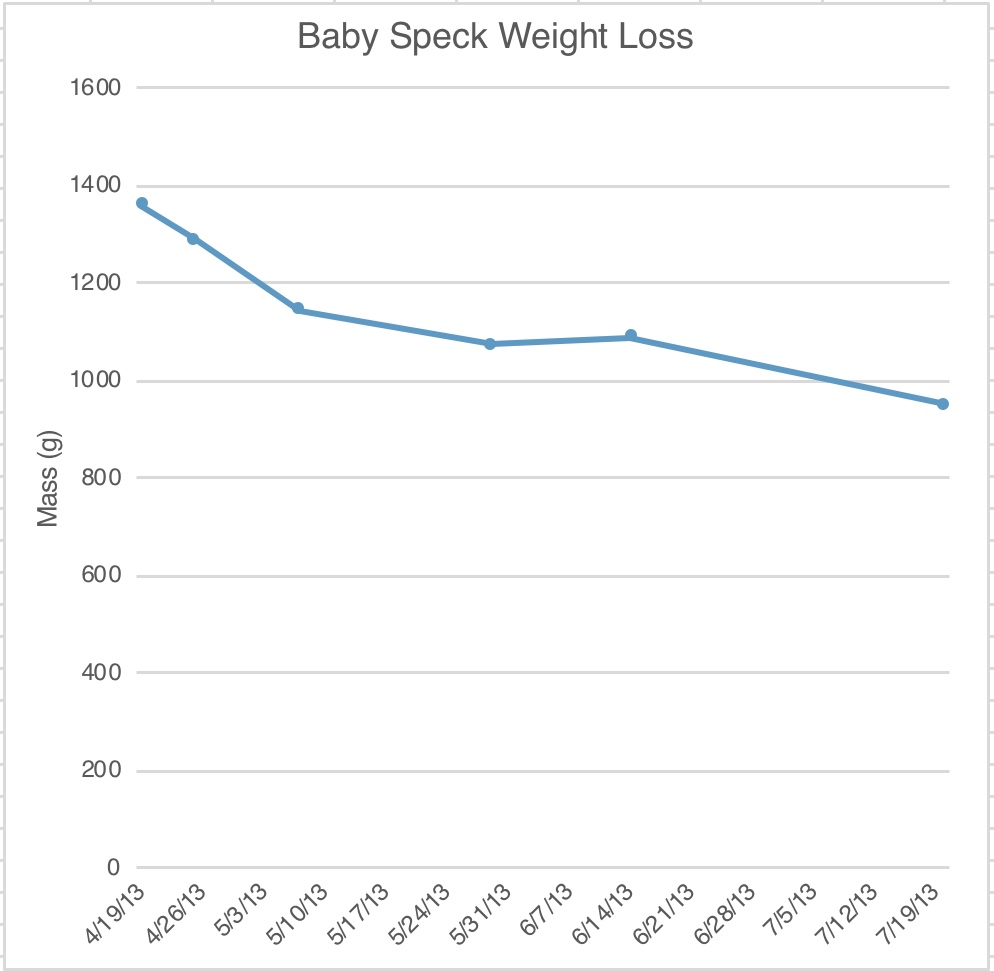

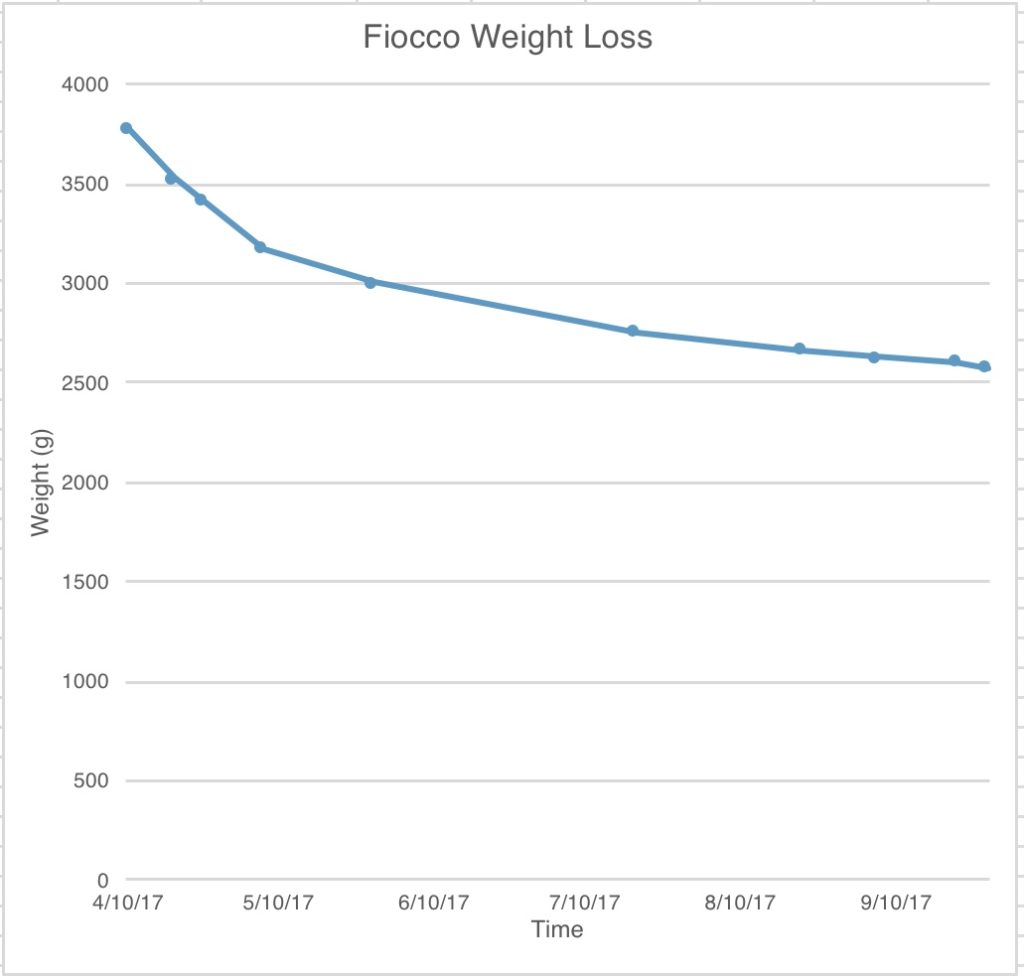

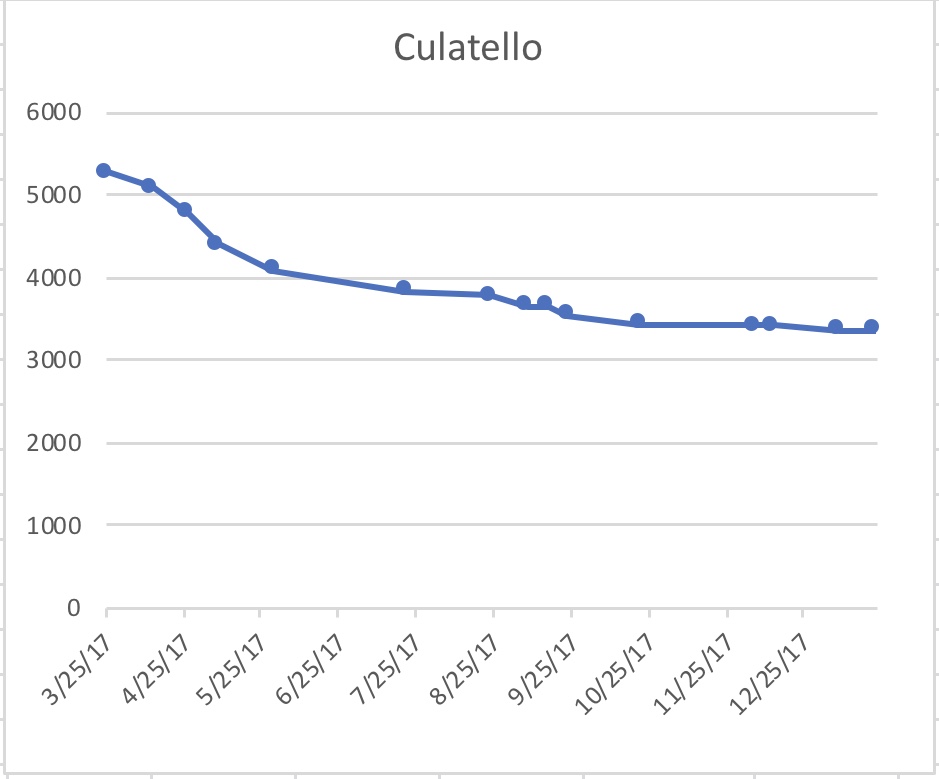

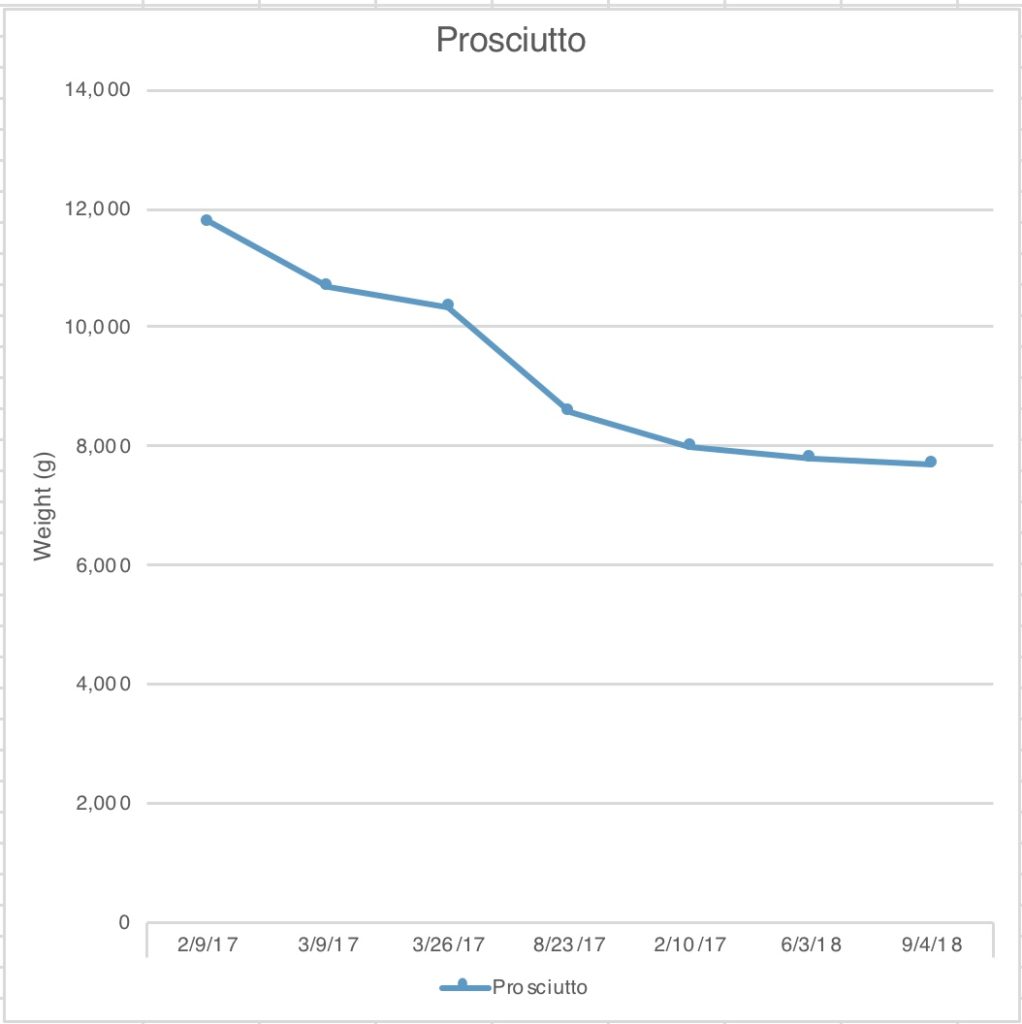

Here, the hard part is the waiting. You are shooting for ~30% loss, but you also want to allow it to hang for enough time to develop a good flavor. I try to leave my fiocco hanging for at least 6 months and the culatello for at least 9 months, a year if I can handle it.

First, I pulled the rumpetto, or baby speck.

After the rumpetto, I pulled the fiocco.

Finally, it was time to pull the culatello.

Tasting

The nice part about curing the all 3 cuts (the rumpetto, the fiocco, and the culatello), is that the rumpetto is done after a short 3 months and the fiocco is done after 6 months, which allows you to satisfy your taste bud curiously about how the process went.

The rumpetto was cut into first.

The smoky fat combined really well with the alpine spices in this baby speck.

The first time I cut into the fiocco I was shocked.

After hearing about how it was the poor step sibling of the culatello, I wasn’t expecting too much. It was great. A nice strong flavor, and well balanced meat to fat ratio.

Cut forward 6 months to the culatello. When I cut open the culatello I think my jaw dropped. Jaw dropping beauty and flavor to match.

It was only then when I realized why the fiocco was called the ugly step sibling of the culatello. Not because the fiocco isn’t great, but because the culatello is SO fantastic. It’s hard to describe the flavor, but the balance of earthy sweetness with salty funk and smooth fat is the ultimate experience.

It’s great served by itself, with some crusty bread, or with some melon. Just make sure you have another one in the making, because it won’t last long!

Disclaimer: Meat curing is a hobby that comes with inherent risks. We can all do things to limit this risk by educating ourselves about the process and the utilizing the safest known methods to create our products. This website is for educational purposes only, and all experimentation should be done at each individuals own risk.