Cure #1 and #2:

You will see the item “Cure #2” in a lot of my curing ratio tables. Cure #2 is a slow acting cure; composed of salt, sodium nitrite (6.25%) and sodium nitrate (1%). It may be colored pink in order to distinguish it from normal table salt. It is used in meats that will be curing over a longer period of time.

Cure #1 is a fast acting cure, used for meats that will be slow cooked and will not undergo a long term curing and drying process. It also may be colored pink in order to distinguish it from normal table salt. This involved meat such as bacon, corned beef, and ham. It is composed of salt and sodium nitrite (6.25%).

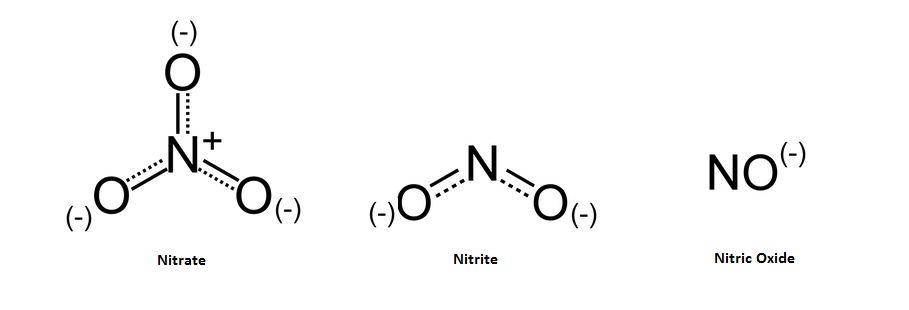

In cured meats, nitrates are slowly reduced over time into the sodium nitrite form, which helps to keep the cure #2 active for long term curing. Sodium nitrite is further converted to nitric oxide. (https://examine.com/supplements/nitrate/)

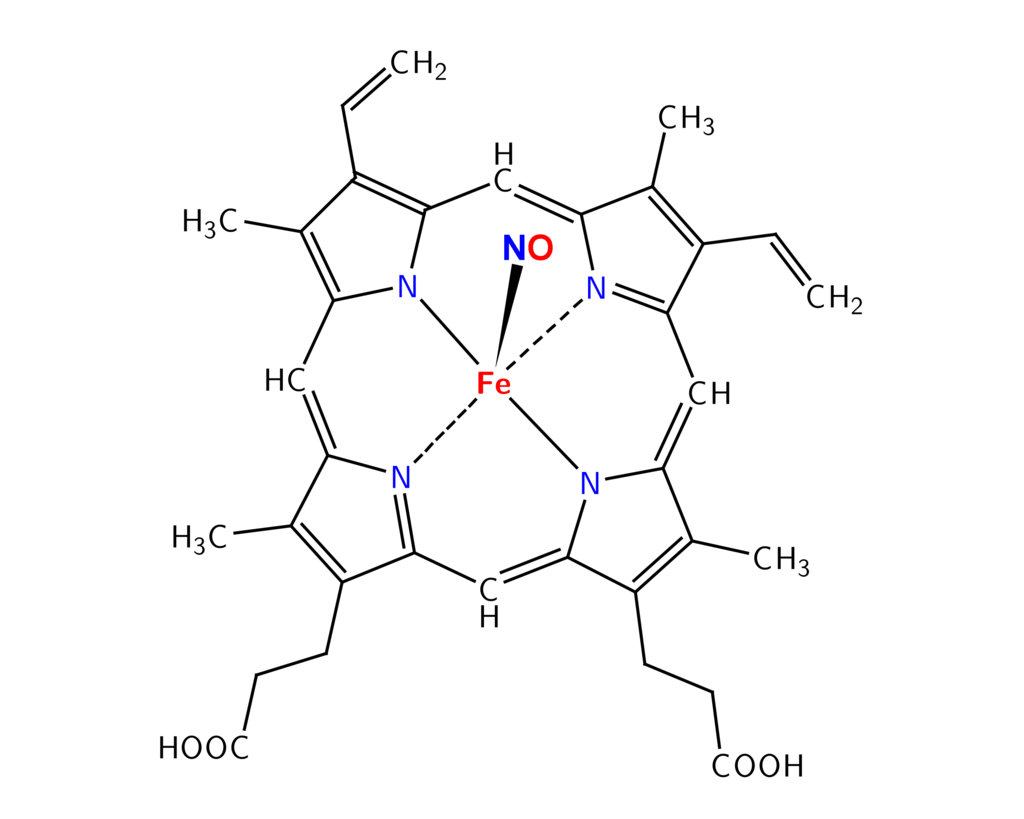

Research has shown that NO can then bind to the Fe (iron) molecule which is in the center of the myoglobin protein, a protein that is found in muscle cells.(https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Curing_%28food_preservation%29)

This is responsible for the red color of cured meats, which will turn pink if heat is applied in a cooking process. (http://ps.oxfordjournals.org/content/48/2/668.abstract)

In addition to the important role that nitrates and nitrites play in creating the characteristic color and flavor of cured meats, nitrates and nitrites are used in order to prevent the growth of harmful bacteria, such as Clostridium botulinum whose toxin can have devastating effects when ingested. (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6751698) This role of nitrates and nitrites make them essential in meat curing.

Some people are opposed to the addition of nitrates in their meat, which is a personal preference, but I believe that they make the process safer and at these levels do not pose an unusual threat level. To quote from MeatSafety.org (http://www.meatsafety.org/ht/d/sp/i/45243/pid/45243),

“The amount of nitrate in some vegetables can be very high. Spinach, for example, may contain 500 to 1900 parts per million of sodium nitrate. Less than five percent of daily sodium nitrite intake comes from cured meats. Nearly 93 percent of sodium nitrite comes from leafy vegetables & tubers and our own saliva. Vegetables contain sodium nitrate, which is converted to sodium nitrite when it comes into contact with saliva in the mouth.”

For example, celery is a food that is high in nitrates. Some people use celery juice to cure meat. Make no mistake; the use of celery juice IS the addition of nitrates. Additionally, there is no quantification involved when using celery juice, so levels of nitrates varies. This means, in some cases the meat will not be safe from threats such as botulism toxin, while in others, the levels of nitrates will far exceed those that are recommended. I find that it is better to know the levels you are adding and be smart about knowing what goes into your food.

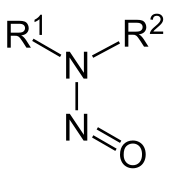

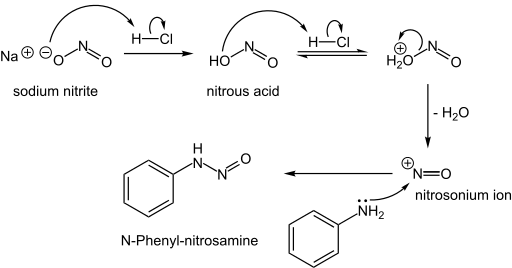

The problem does not lie with nitrates or nitrites, but rather with a product that they can form: nitrosamines.(https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nitrosamine)

This occurs when nitrites interact with amines, commonly found in protein such as meat. In acidic conditions (such as the stomach) or at high temperatures (such as the frying pan), pathways that lead to the formation of nitrosamines can be favored. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nitrosation)

This reaction only occurs when nitrites and amines are present, and the environment favors this reaction. This is why, even though leafy greens have high levels of nitrates, they don’t have high levels of nitrosamines. You can check out the levels of nitrates, nitrites, and nitrosamines in different food and drink items in this free research article table: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2669451/table/T2/

The formation of nitrosamines can be inhibited by the addition of compounds that interfere with this reaction. Certain anti-oxidants are able to do this. To quote a research article that has been published on this topic (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/m/pubmed/8304939/):

” Such inhibitors include vitamins C and E, certain phenolic compounds, and complex mixtures such as fruit and vegetable juices or other plant extracts. Nitrosation inhibitors normally destroy the nitrosating agents and, thus, act as competitors for the amino compound that serves as substrate for the nitrosating species. “

This effect has been noticed by producers of cured meats, and some people add in components to limit the formation of nitrosamines in their cured meats. The most common addition is sodium ascorbate (at 0.15% of total meat weight), which is a salt of ascorbic acid (Vitamin C), and is used due to its slower rate of reaction compared to ascorbic acid itself. The hope is that the addition of sodium ascorbate will bind to any excess nitrites, preventing them from binding to amines and going on to form nitrosamines. I have not used sodium ascorbate in any of my products yet, but it is something that I have been considering.

So, what is the takeaway? Unfortunately, the ingestion of nitrosamines has been weakly linked with certain forms of cancer.(http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26633477) Research is ongoing, but it does make sense to know the risks and be smart about what you ingest. Creating your own products, just like cooking your own food, is the best way to be certain about what you are putting into your body.

Disclaimer: Meat curing is a hobby that comes with inherent risks. We can all do things to limit this risk by educating ourselves about the process and the utilizing the safest known methods to create our products. This website is for educational purposes only, and all experimentation should be done at each individuals own risk.